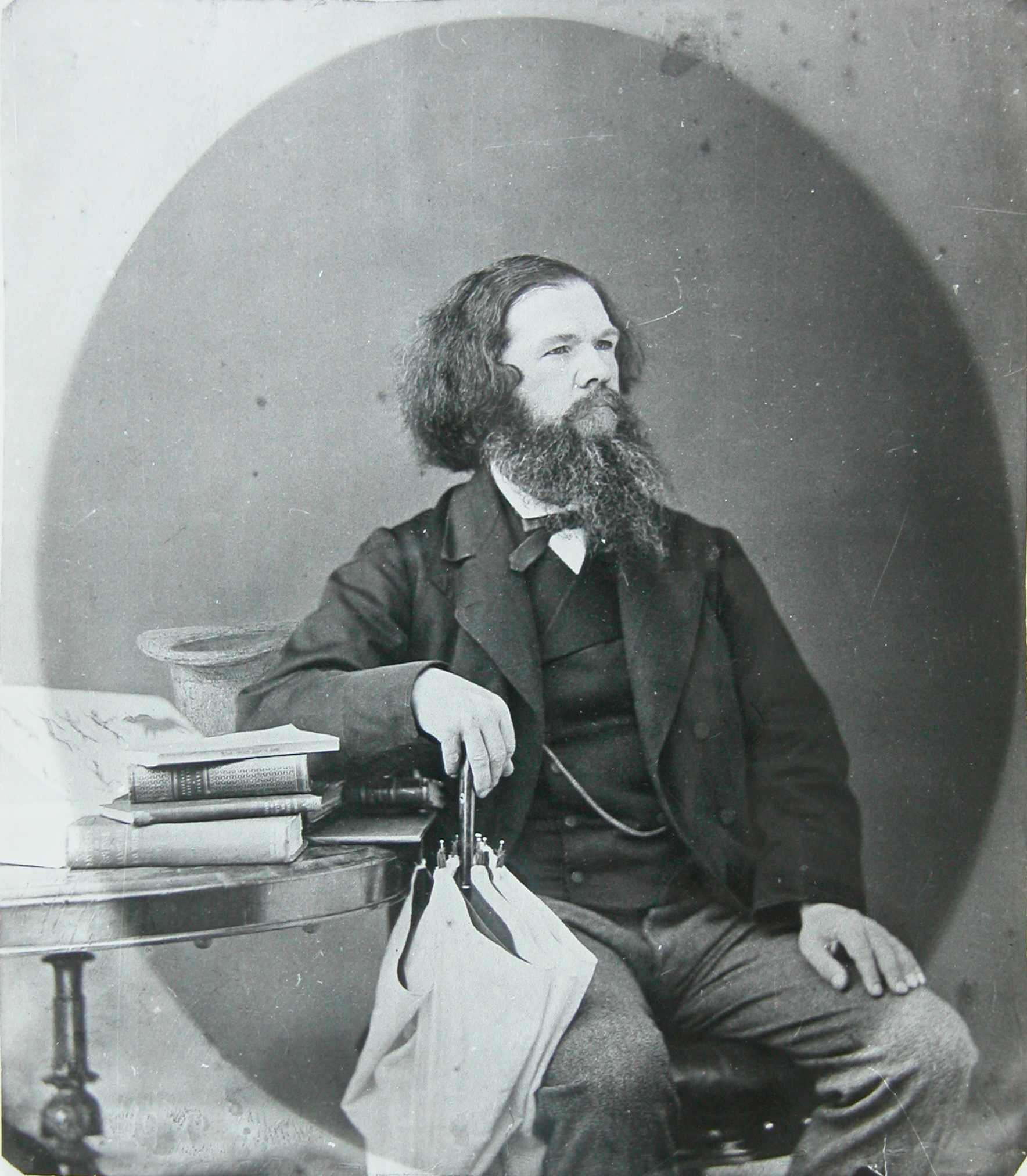

Wilhelm Heinrich Immanuel Bleek was born in Berlin on 8 March 1827. He was the eldest son of Friedrich Bleek, professor of theology at Berlin University and then at the University of Bonn, and Augusta Charlotte Marianne Henriette Sethe. He graduated from the University of Bonn in 1851 with a doctorate in linguistics, after a period in Berlin where he went to study Hebrew and first became interested in African languages.

Bleek’s thesis featured an attempt to link North African and Khoekhoe languages – the thinking at the time being that all African languages were connected. After graduating in Bonn, Bleek returned to Berlin and worked with a zoologist, Dr Karl Peters, editing vocabularies of East African languages. His interest in African languages was further developed during 1852 and 1853 by studying the work of Professor K.R. Lepsius, an Egyptologist whom he met in Berlin in 1852.

Bleek was appointed official linguist to Dr W.B. Baikie’s West African expedition in 1854. Ill health (a tropical fever) forced his return to England, where he met the recently appointed governor of the Cape, Sir George Grey, and John William Colenso, the newly consecrated Anglican bishop of Natal, who invited Bleek to join him in Natal in 1855 to help compile a Zulu grammar. In Natal he met Donald Moodie (author of The Record) and heard about those known as Bushmen of the Drakensberg. After completing Colenso’s project, Bleek travelled to Cape Town in 1856 to become Sir George Grey’s official interpreter as well as to catalogue his private library. Grey had philological interests and was Bleek’s patron during his time as governor of the Cape. The two had a good professional and personal relationship based on an admiration that appears to have been mutual. Bleek was widely respected as a philologist, particularly in the Cape. While working for Grey he continued with his philological research and contributed to various publications during the late 1850s. Bleek requested examples of African literature from missionaries and travellers such as the Rev. G. Krönlein, who provided Bleek with Nama texts in 1861.

In 1859 Bleek briefly returned to Europe in an effort to improve his poor health but returned to the Cape and his research soon after. In 1861 Bleek met his future wife, Jemima Lloyd, at the boarding house where he lived in Cape Town while she was waiting for a passage to England, and they developed a relationship through correspondence. It was this correspondence that gives us much Lloyd family history, including the sad story of the daughters’ childhoods and their life with their father in Natal. Jemima returned to Cape Town from England the following year, having agreed to marry Wilhelm. The marriage took place on 22 November 1862. The Bleeks first lived in New Street and thereafter Grave Street in the Gardens, then at The Hill in Mowbray, moving again in 1875 when they purchased Charlton House.

Apart from his work with the Grey library Bleek contributed opinion pieces to Het Volksblad between 1862 and 1866. His first column appears a few months before his wedding to Jemima Lloyd and the last (the 75th) a few months after he engaged his first |xam instructor Adam Kleinhandt. The writing of these leaders would have provided a small income to the newly married couple. The topics Bleek addressed (among many others, and often in a tone of outrage) ranged from the blundering of Sir Philip Wodehouse, to Scotch superstition, to the Free State Basotho conflict, to the possible outbreak of the Prussian-Austrian war, to rainmaking versus ‘fixing a day of humiliation and prayer’. In the former he refers on Wodehouse’s lengthy speech to Parliament commenting on his “incapacity to deal competently with questions of any high political bearing,” and in the latter he berates the government for a “prostitution of the religious instincts of man” by “exceeding its province” in calling for a day of prayer for rain. He was deeply concerned with the governance of the city and the colony and commented on a range of issues relating to public health, such as the condition of cemeteries, the dangers of burial grounds expanding on the slopes of the Lion’s Rump, the need for improved life-saving equipment, and the combat of cholera. He also proposed some remedies for unemployment, and argued vociferously against a bill related to women’s rights of inheritance which he said to be “a totally unjustifiable assault on the rights of the weak and least protected”. He also published the first part of his book A Comparative Grammar of South African Languages in London in 1862. The second part was published in London in 1869. Unfortunately, much of Bleek’s working life in the Cape, like Lucy Lloyd’s after him, was characterised by financial hardship, which made his research even more difficult to continue with.

Lucy Lloyd joined the Bleek household later in the 1860s, and the two other sisters and one of their half-sisters came sometime later. When Sir George Grey was appointed governor of New Zealand he presented his collection of books to the South African Public Library on condition that Bleek be its curator, a position he occupied from 1862 until his death in 1875.

Bleek’s first contact with Bushmen was with prisoners at Robben Island and the Cape Town Gaol and House of Correction in 1857. He conducted interviews with a few of these prisoners, which he used in later publications. These people all came from the Burgersdorp and Colesberg regions and spoke variations of one similar sounding ‘Bushman’ language. Bleek was particularly keen to learn more about this language and compare it to examples of ‘Bushman’ vocabulary and language earlier noted by the traveller Henry Lichtenstein and obtained from missionaries at the turn of the nineteenth century.

In 1863 the magistrate Louis Anthing introduced the first ǀxam speakers to Bleek. He brought three men to Cape Town from the Kenhardt district to stand trial for attacks on farmers (the prosecution was eventually waived by the attorney-general). In 1866 two Bushman prisoners from the Achterveldt near Calvinia were transferred from the Breakwater Convict Station to the Cape Town prison, making it easier for Bleek to meet them. With their help, Bleek compiled a list of words and sentences and an alphabetical vocabulary. Most of these words and sentences were provided by Adam Kleinhardt.

In 1870 Bleek and Lloyd, by now working together on the project to learn the |xam language and record personal narratives and folklore, became aware of the presence of a group of 28 ǀxam prisoners (known then as ‘Cape Bushmen’) at the Breakwater Convict Station and received permission to relocate one prisoner to their home in Mowbray so as to learn his language. The prison chaplain, the Rev. George Fisk, was in charge of choosing this individual – a young man named ǀaǃkunta. Because of his youth, ǀaǃkunta was thought to be unfamiliar with much of his people’s folklore, and an older man named ǁkabbo was then permitted to join him. ǁkabbo became Bleek and Lloyd’s first real teacher, a title by which he later referred to himself (Bleek referred to him as ‘my instructor’). Over time, members of ǁkabbo’s family and other ǀxam families lived with Bleek and Lloyd in Mowbray and were interviewed by them. Many of the ǀxam instructors Bleek and Lloyd were related to one another. Words, phrases and stories were recorded phonetically and then translated either at the same time or later, often with the assistance of other |xam. This form of recording provides valuable insight into the development of the project and the changes in understanding over time.

Bleek, along with Lloyd, made an effort to record as much personal history as possible. This included genealogies, places of origin, and the customs and daily lives of the informants. Photographs and measurements (some as specified by Thomas Huxley’s global ethnographic project) were also taken of the instructors in the early years in accordance with the norms of scientific research at the time in those fields. Later on more intimate and personal photographs and painted portraits were commissioned one of some of the ǀxam collaborators.

Although Bleek and Lloyd interviewed other individuals (Lloyd doing this alone after Bleek’s early death in 1875), most of their time was spent interviewing only six individual ǀxam contributors. Bleek wrote a series of reports on their language, literature and folklore, which he sent to the Cape secretary for native affairs. This was in the first place an attempt to gain funding to continue with his studies and then also to make the colonial government aware of the need to preserve Bushman folklore as an important part of the country’s heritage and traditions. In this endeavour Bleek may well have been influenced by Louis Anthing.

Bleek died in Mowbray on 17 August 1875, aged 48, and was buried in the Wynberg Anglican cemetery in Cape Town along with his two infant children, who had died before him. His all-important work recording the ǀxam language and literature was continued and expanded by Lucy Lloyd, as well as by his wife Jemima. A deeply moving letter survives in which his widow, Jemima describes the night of his death. Dia!kwain was present in the house that night.

In an obituary in the South African Mail of 25 August 1875, he was lauded in the following terms: ‘As a comparative philologist he stood in the foremost rank, and as an investigator and authority on the South African languages, he was without peer.’ But he was also a man who inspired the devotion of the Lloyd sisters, ensuring his future legacy.

Cite: Skotnes, P. 2025. Wilhelm Bleek. In ǃkhwe-ta ǃxōë Digital Bleek and Lloyd. Centre for Curating the Archive: https://digitalbleeklloyd.uct.ac.za/whi-bleek.html