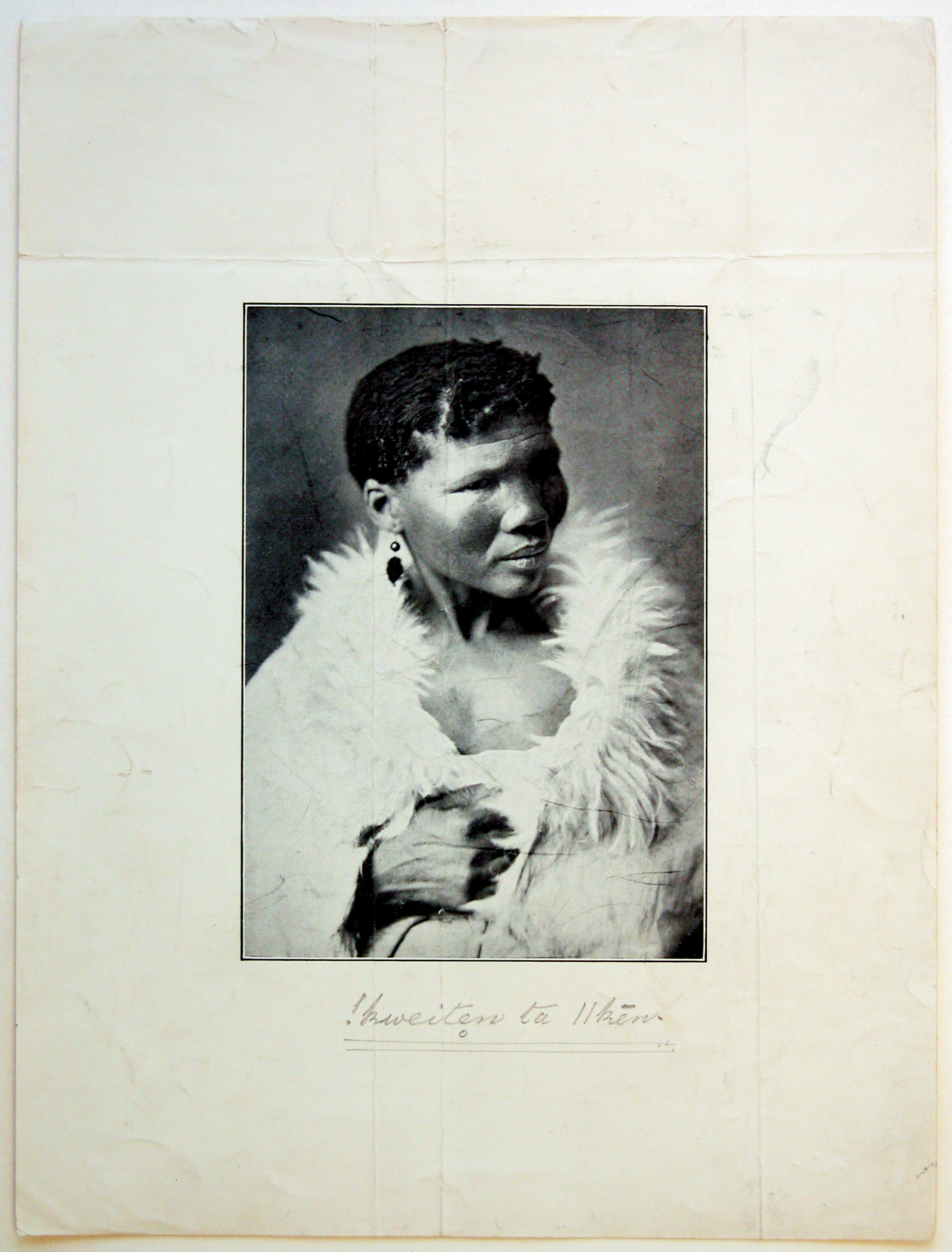

Like her husband ǂkasin, ǃkweiten ta ǁken, or Rachel, came from the region of the Katkop mountains. She was Diaǃkwain’s sister and accompanied the two men to Cape Town when they returned in June 1874. She and ǂkasin had had five children, the eldest and youngest of whom had died, and while ǂkasin was imprisoned she had taken up with another man and had borne another son, Gert. Gert’s father, however, died before ǂkasin’s release. When ǃkweiten ta ǁken travelled to Cape Town two of her younger children, boys aged 2 and 6, accompanied her, and a further two joined her in October of the same year.

The seven ǀxam staying at Mowbray must have placed substantial additional strain on the household budget, but Lucy Lloyd was pleased to have the opportunity to interview a woman whose own experience could throw light on the routines and customs associated with women’s lives. But ǃkweiten ta ǁken could not make herself happy at Mowbray and her interviews reveal little of the expansiveness and expressive power of her brother’s.

Her contribution is not, however, without interest. She did record some stories about ’new maidens’ (young girls in seclusion at the time of their first menstruation) and the rain animal who had a special relationship with them. There are also details of the foolishness of men, in particular one rather tragic narration in which a man, enraged that his wife appeared to be eating too much, tore open her stomach only to find she was pregnant. Greatly upset, he attempted to sew the wound together but was unable to undo his foolish action and the harm he had inflicted. She also provided an intriguing narrative of the Early Race and the power of the Leopard Tortoise to cause a foolish man’s hands to wither and decay.

ǃkweiten ta ǁken was interviewed for only a very short period and, keen to return home despite her apparently close relationship with her brother Diaǃkwain, she left Cape Town with her husband and children on 13 January 1875.

Cite: Skotnes, P. 2025. ǃkweiten ta ǁken. In ǃkhwe-ta ǃxōë Digital Bleek and Lloyd. Centre for Curating the Archive: https://digitalbleeklloyd.uct.ac.za/kweiten-ta-ken.html