When ǀuma was a young child he lived with his parents and siblings. His father had taken a second wife and the children from that union lived with him too. His mother built the grass hut they slept in, and she collected fruit and kernels and brought water from the river. His father hunted elephants by trapping them in game pits and then he traded the ivory. Hundreds of elephants were shot in his country in the last year that ǀuma spent with his parents and thousands of pounds of ivory traded. ǀuma remembered with special affection the fruit of the ‘ǀkui’ tree, and its kernels (LL121: 10105v).

One day that ǀuma recalled well, the neighbouring Makoba (or Yeyi) arrived, snatched him and his half-brother ǂni ǁnau and dragged them away. ǀuma’s mother and the mother of his half-brother tried to prevent the kidnapping, pleading with the Makoba to let the children go. The Makoba were unrelenting, and while the women cried and protested, the boys were put into a boat and rowed away. They journeyed for two days and, arriving at their abductors’ place, were given food and slept the first and second nights there. On the third day, ǀuma’s father arrived. He remonstrated with the Makoba and demanded the return of his sons. They had done nothing, not stolen their food, he said; they should be returned to their parents. The Makoba threatened ǀuma’s father and he left, returning later with the two mothers. All three then tried once again to secure the release of their children, but again were met with threats and hostility. The three parents spent a last night near the camp of the Makoba, having made a little fire which ǀuma watched burning. Then, next morning, they left the area, leaving the boys behind. Some time later the Makoba took ǂni ǁnau back to his home, where he died, but they kept ǀuma and, as far as we know, he never saw his parents again.

ǀuma was detained by the Makoba for almost six months. He counted the months with the ‘death’ of each new moon. He was not kept hungry but he could not have known much affection, for at the end of six months the Makoba sold him for a gun to a passing Boer trader. ǀuma moved about with the Boer and at times with groups of Boers as they traded sheep and cattle with the Ovaherero. ǀuma remembered the many moons and many suns he observed, to mark the time that he was with the Boers, and he recalled the gift of a little goat. But in the tenth month he failed to prevent some sheep he was tending from escaping and his master beat him so badly that, even though he was far from home and with nowhere to go, he ran away. ǀuma’s heart ached. He dreamed of home and headed off in a direction that might take him there.

‘Messer Karo’, a hunter (Henry Seymour Carew who acted for the trader Axel Eriksson whose ship brought the boys to Cape Town), encountered ǀuma not long after this. He was a white man but not a Boer; losing his hair, yet not an old man. He kept ǀuma with him, and when a previous Boer master of ǀuma’s arrived on horseback at the small grass hut that ǀuma and the hunter were living in, Carew drove him away refusing to give up the boy and, apparently, securing the release of another younger ǃkun boy, Da. ǀuma, Da and the hunter then left the place of the Boers and travelled to another part of the country (LL122: 10225–52v).

ǀuma’s home was said to be in the area north-east of Damaraland, somewhere in the border region of Angola and Namibia. His was a dialect different from that of the Juǀ’hoan, according and lived in the area west or north-west of the Omuramba–Omatako rivers. There was virtually no permanent European occupation of the area at the time although extensive trade networks involved all the people of the region – the San, the Ovambo, the Damara, the Makoba, the Ovaherero, and Boer hunters and traders who ventured into the area on horseback or in wagons. Elephant hunting for food and ivory was important for trade which appeared to serve local as well as long-distance markets. Indeed, pressure from European traders in the south to supply ivory, fur and ostrich feathers ensured a steady supply of firearms, horses and gunpowder into the north. Trade also included beads, pottery, tobacco, dagga and Indian hemp, cattle, and various iron products (LL112: 9280). Even cheap German scent bottles were traded by the San, who used them to make arrowheads (Frere 1882: 328). By the 1880s, the expanding European and American demand for ivory for pianos resulted in the extermination of elephant herds, and big-game hunting drastically reduced wild-life populations (Gordon 1992: 32–8).

ǀuma and Da remained with Henry Carew. They travelled south through mountainous regions, eventually coming upon a camp with grass huts and a wagon and two white men who had with them three Nama. ǀuma and Da were handed over to one of the white men as Carew decided to head back to his home. He left shortly afterwards, apparently promising to rejoin the boys, and Da and ǀuma waited for him, but he did not return. (As this story is told from the boys’ point fo view, it is not clear how orchestrated the boy’s capture was, probably by Eriksson, or whether their arrival at Walvis Bay was fortunitous).

Da, like ǀuma, had been abducted. He was at home with his parents when the Makoba came and took him away. His father was an elephant hunter and his mother worked clay. Whenever Da saw an elephant he would run to fetch his father so that he could hunt and kill it. He knew to be afraid of other people, and he and the other children would run away when they saw strangers. On the day he was abducted he was with his parents, both of whom had tried to wrest him from the attackers’ grip. First his mother was beaten and killed and then his father, who had tried to shoot at the Makoba, was murdered. Other children were also taken by the Makoba but they were thrown into the river and eaten by crocodiles. Only Da survived (LL122: 10274–9, 10282–92, 10253–60).

ǀuma and Da, the white men and the Nama travelled south and came at last to Walvis Bay. Carew never came back for the boys, and the white man with whom they had travelled left them at the harbour with the instruction to board a certain ship where they would find food. The boys stowed away on the ship, which soon set sail for Table Bay.

When ǀuma and Da arrived in Cape Town, they generated much curiosity in the people who met the boat at the harbour. One person offered them grapes and then, apparently, tried to persuade them to go with him. ǀuma refused and the boys joined a group of ‘Berg Damaras’ (who had been brought into the Cape under a labour importation scheme by Cape Commissioner Palgrave)who were heading away from the harbour. Eventually they met up with a Dutch-speaking white man who interrogated the boys and took them to his house where he gave them bread to eat. On 25 March 1880, they were placed in the care of Lucy Lloyd and Jemima Bleek in Mowbray.

In September the previous year, Lucy and Jemima had provided a home for two older dispossessed ǃkun boys. These shared a room in the house in Mowbray and the new boys joined them. Lucy made quick progress with learning the new language so that when ǀuma and Da arrived she could converse a little with them. The older boys had also travelled from north of Damaraland and told Lucy many stories about the things they saw and remembered from their home.

Less is recorded about how these two boys – Tamme, who was in his mid-teens, and ǃnanni in his late teens – came to Cape Town. Both blamed the hated Makoba for the loss of their families and home. Tamme explained that he was at home drinking water with his mother and other people who all lived near a river or lake, ‘a great water’ (LL111: 9216). The Makoba arrived in their boat and, calling Tamme by name, commanded him to go to their house. Tamme’s mother had previously gathered food from ‘her country’ and had given this to the Makoba in exchange for ‘things’, but Tamme was suspicious of them and refused to enter their house. The Makoba, it seems, depended to some extent on this barter with the ǃkun, for when it was very rainy and food failed, Tamme said they would eat their dogs. Eventually, with the promise of food, Tamme entered the house and soon thereafter was ‘given’ by the Makoba to the Ovambo. How he found his way to the Cape is not recorded, and even less is known about the circumstances of ǃnanni’s dispossession.

Various descriptions by ǃnanni and Tamme of the people of the region give a sense of the close interactions between people of different groups and the ways in which the young boys identified difference. They said that many different peoples and groups of ǃku (‘Bushmen’) were to be found in their country. These included the Makoba (who, Tamme said, killed the Ovaherero), the ǀnani (who were different, as the Makoba were, but also resembled the Ovaherero, and were tall and black and possessed long guns), the Shimbari (whom Tamme saw when he was a child), the ǀna (who resembled the ǃku), the Brikua yao (a different kind of Bushmen), the ǀgeriku yao (who resembled the Ngoba), the Benza (who resembled the Makoba), the Bugu Bugu (who resembled another kind of ǃku), the ǁhi (‘another kind of Bushmen’), the ǂam (‘another kind of Bushmen’), a group of Bushmen who spoke like Berg Damaras, and the ǃuhobba (who were black). Tamme saw all of these people.

Tamme also said that the ǀgeriku Bushmen did not speak in the same manner as the Ovambo and the Ovaherero (a manner called ‘ǃhobba’, which meant ‘to speak in a loose-tongued fashion’). They spoke ǃnanni's language. They did not understand the Makoba (‘ǃhobba’ speakers). The Hai ǁum were Bushmen, he said, who also spoke Nama. The ǃgu ǃxani Bushmen were black and resembled the Berg Damara. The Ash (or ǂgua ǃku) Bushmen, the Bugu Bugu ǃku, lived far away. ǃnanni said that on the tenth month of travelling with the Bugu Bugu ǃku he saw their houses. These people were white and slept in the ashes. ǃnanni said they resembled ǀhanǂkass’o (a ǀxam speaker), and were not tall. The Sun Bushmen were called the ǀkam-ssin ǃku. The ǂgua-ssin ǃku were tall people and not very black. ǃnanni spoke their language. The Pit(-making) Bushmen (or ǃkorro-ssin ǃku) were not black and spoke ǃnanni's language. There were many of them and they lived near a large body of water. The ǁhe ǃnum shu spoke the same language as the Makoba. The Ovambo and the Ovaherero wore the same kinds of shoes. ǃnanni described the dress worn by Omuherero men and women. There were also Bushmen called the Yabbi, and ǃnanni himself was a Sun Bushman (or ‘sun child’), while his mother was a ǀgeriku Bushman woman. The ǂhunni-me Bushmen resembled the Makoba and wore a ‘ǃku’ (a type of girdle), and in Tamme’s mother’s country, which was far away, there were people who killed the Makoba.

The ǃkun boys’ memories of home were, unsurprisingly, full of trauma. Given the fierceness of trade, the competition for ivory, the seemingly poor relationships with so many neighbouring groups, the widespread access to firearms and dagga, and the apparent absence of any rule of law, their exposure to violence, homicide, grief and practices for burying the dead was extensive. They feared ghosts, who could be violent, the darkness, and lions in the night, who were said to live in abandoned houses. They described others who killed them and the punishment for theft, which was death by fire or knife. ǃnanni described how a man would kill his wife by slipping a poisoned arrow into her bed at night if he was dissatisfied with the food she had collected. He also told of how his mother and father cried after the death of their son and how he and his elder brother wept too. ǃnanni dictated a song about the loss of a son and also the song of the ‘ǃna ǃna’rishe’ bird, who sang about the disappearance of people from its country.

He also remembers his uncle who died in a Makoba house and the violent fight that followed his death. Tamme described how his aunt was trampled to death by elephants and how his father had to sleep in ashes after killing someone. Tamme’s cousin also died and was buried with trees piled on the grave. ǀuma said that when his uncle died he was buried by his people and his aunt cried, but when a stranger died they would not bury him.

Many of the narratives that Tamme, ǃnanni and ǀuma told Lucy Lloyd were focused on a character called ǀxue – an entity that is not a person but becomes a person and many other things. Like the rest of their memories, these are full of longing, death and grief, fear, the love and hatred of parents and children, and betrayal. ǀxue was everywhere and everything. He was water in the shadow of the tree, and a son weeping for his father. He was a dead child and a dead elephant eaten by vultures. He was an Omuherero crying of thirst. ǀxue was ‘gabaka’, a fungus on a tree, of which men were afraid. He was a little fly and a large black butterfly. ǀxue was a being who died from falling out of a tree and who called and called for his father, but his father was silent and ran away. ǀxue cried. ǀxue’s mother beat and wounded his father, blood running from his head. ǀxue was a mouse shot at by his father, and he was not a mouse and shot his father and his mother kicked him and stood, looking at him. ǀxue was powerful and weak, brave and afraid, vindictive and forgiving.

Life at Mowbray was a far cry from life along the trade routes of northern Namibia. In the lists of words that Lucy first recorded with the boys, one gets a sense of things that were to be observed in and around the house. The cow eats; the dog barks; the cat eats the mouse; I blow the lighted candle; I washed the plates; the wire is here, the wood’s wire it is (of a mousetrap); I am sleepy; I carried the cat in a basket; the white cloud (on top of Devil’s Peak); a quarrel (between a cat and a dog); the horse holds the kettle in its mouth; Jantje takes Tamme to sleep; ǃnanni’s composition of a little song to sing while weeding in the garden; and his musings over the meaning of the cock crowing in Mowbray and the response of another in nearby Rondebosch.

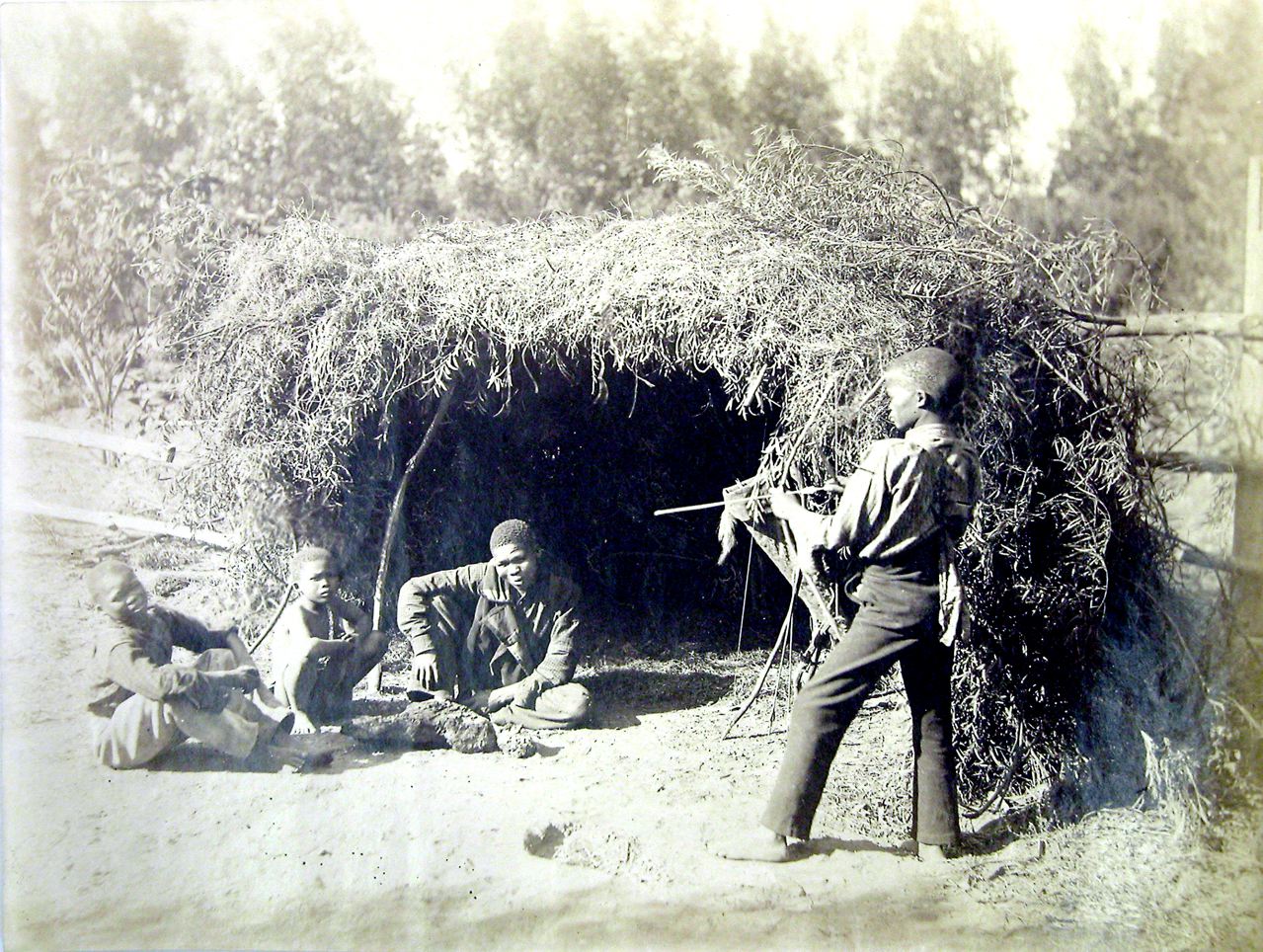

Lucy took the boys into town to the South African Museum and they named the insects and animals they saw there. She also took them to the local photographer for whom they posed, though there is some sense that the experience was not without discomfort. One image of ǀuma wearing a skin apron, beads and carrying a bow and arrows, bears the note on the back written by Lucy: ‘In this picture he is shrugging his shoulders from shyness.’ At home they built two grass huts in the garden to play in – one for themselves and one for the other children in the house. They made bows and arrows, which rendered them, apparently, the envy of the neighbourhood children, and they would trade the bows for tobacco or marbles. On Sundays they would gather inside, an occasion they thought a great treat, and Jemima would play the piano for them. A favourite was Handel’s Dead March from Saul.

Perhaps the most touching and poignant legacy of the four ǃkun boys (but also, as Magdaleen du Toit shows in her PhD thesis and online site, the demonstration of their astonishing knowledge of botany and bush lore) is the collection of hundreds of drawings and watercolours they made. These were done on loose sheets and in drawing books, and were almost all annotated by Lucy with descriptions of the subject matter or numbered notes. All four boys made drawings and painted, and the images reveal a surprising lack of evidence of violence, in contrast to the stories, drawing attention rather to the fruits and trees, foods and animals that they recalled from home. Images included depictions of the sky with stars, of routes around home, of plants with white flowers and shallow roots, of giraffe, fish, a leopard with the skin of an antelope (apparently in its mouth), a boy asleep in the sun in the shade of a tree, various animals and ‘mere things’.

ǃnanni and Tamme stayed with Lucy and the Bleek family for two and a half years, ǀuma for just under two years, and Da for four. The elder boys left Mowbray on 28 March 1882 to travel back home in the company of Axel Eriksson. Da and ǀuma were both found employment. It is not known what became of the boys, although letter in the Cape Archive found by Marlene Winberg indicated that Lucy Lloyd arranged for the return to |uma of a handkerchief he had left behind and that she worried he would miss.

Forty years later Lucy Lloyd’s niece Dorothea Bleek visited ǃkun communities in Angola and northern Namibia. She found some groups of them in a greater state of social disintegration, if this were possible, than that which pertained in the 1870s. It is not clear whether she reached the precise areas that the ǃkun boys came from, nor if she met anyone from their broader communities in the Namibian and Botswanan gaols she visited. However, it appears that in the general region there were still dense trade and bartering networks with Ovambo, Herero, Englishmen and Boers, and the Makoba were still the hated neighbours. One informant told Bleek they would put ‘the Bushmen in the pot’ and then ‘roast and eat the people’ (DB19: 487). There were also many stories of violence, of children that died, and much about death and burial practices. The Nama and others were said to carry off women and abduct children and treat them cruelly, lions and spirits would kill people, and there were many comments on ‘sorcery’ and the actions of ghosts who rose from their graves and who would eat children. Already there was a trade in medicinal plants and the beginning of the exploitation of San intellectual property indicated by mention of a German doctor who was said to have come to dig up roots. Smallpox was a cause of death and medicinal treatments were described (Bleek 1910–38, Bleek 1928).

In my own trip to visit remaining ǃkun communities in southern Angola in 2024 almost 100 years later with linguist Matthias Brenzinger and Bernhard Weiss, the situation was not much better. Small groups live in small homesteads surrounded by cattle owning people who have made hunting and gathering impossible. There is still pride in speaking the language, but as one woman told me, “we don’t tell stories any longer, our only story is hunger”.

The testimony and life stories of Tamme and ǃnanni, ǀuma and Da give some sense of the longer history of marginalisation and abuse that the San were and still are subjected to, and an insight into the ways in which their communities were part of a much wider world of trade, exchange, interaction and, occasionally, cooperation.

Cite: Skotnes, P. 2025. ǃnanni, Tamme, |uma and Da. In ǃkhwe-ta ǃxōë Digital Bleek and Lloyd. Centre for Curating the Archive: https://digitalbleeklloyd.uct.ac.za/kun-boys.html