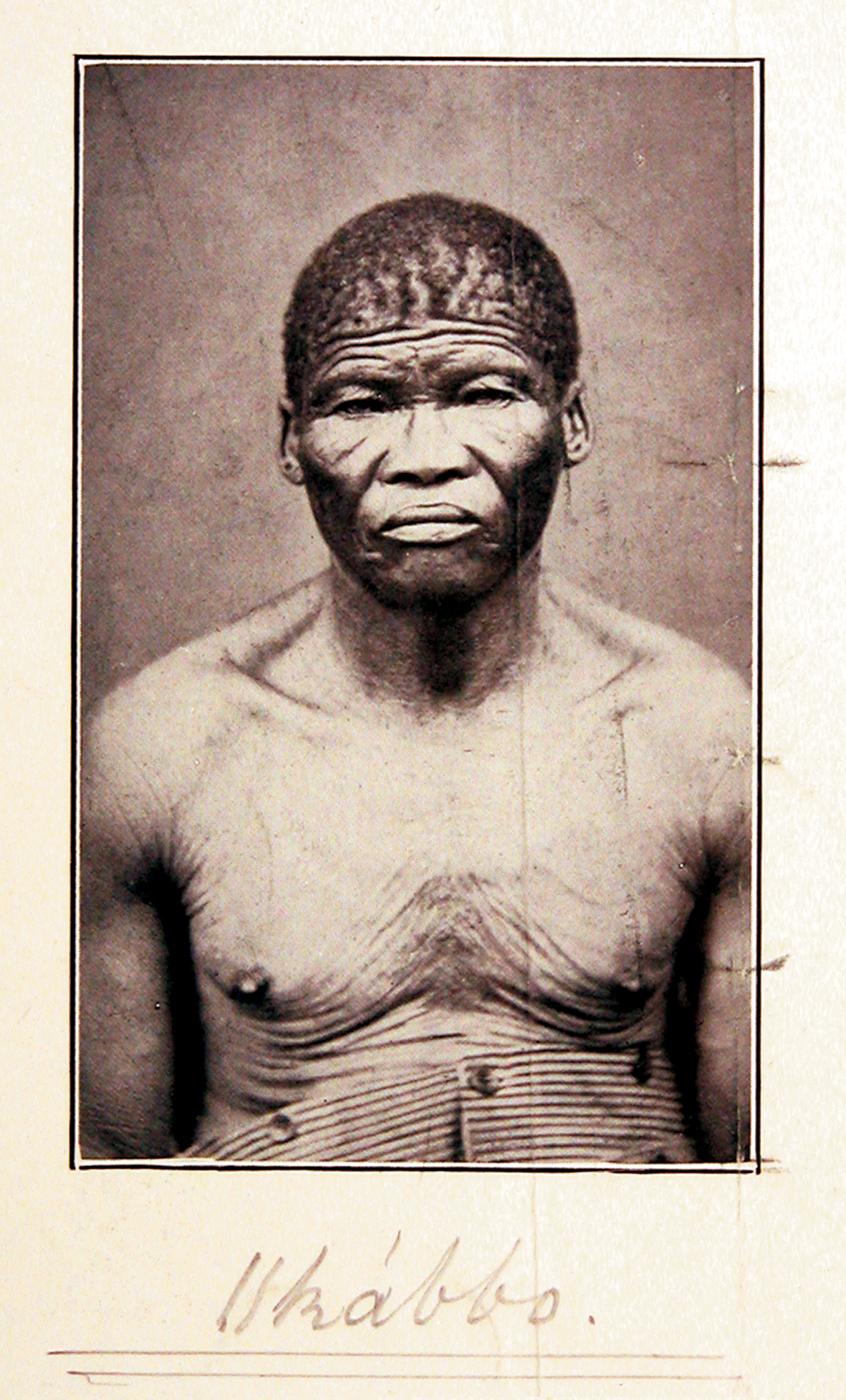

Of all the ǀxam who worked with Bleek and Lloyd, ǁkabbo looms largest as teacher, as elder of his community, as the embodiment of the injustice, indignity and cruelty that was visited upon the ǀxam. It was he who memorably told Lucy Lloyd that he wanted his stories to be known by way of books, a wish that has inspired many remarkable publications. It is also his descriptions of his arrest and incarceration, his home, his longing to return to his wife, his characterisation of stories as things which float on the wind, that make some of the most poignant reading in the archive. But ǁkabbo was not just a victim of the turbulent circumstances of his time. As Anthony Traill argues he was deeply embroiled in the conflict between Boers, Basters, Korana and the colonial government, so that his arrest for stock theft was not just the outcome of a desperate act of hunger (though this may well have been part of it) but rather the result of a war of resistance that he and the gang of men to which he belonged were waging in the Strandberg region. ǁkabbo (literally ’Dream’), whose other names were ǀuhi-ddoro or Jantje Touren or Tooren, lived with Bleek and Lloyd between February 1871 and October 1873. ǁkabbo’s people were the Ss’wa ka ǃkui or ’Flat Bushmen’ (like ǀaǃkunta’s, the ǀxam who lived on the plains). He was from an area close to the Strontbergen called the Bitterpits, and the water of his home was water that was inherited from his father and his father’s father. He had been arrested and tried for stock theft, being found guilty in October 1869 and sentenced to two years with hard labour at the Breakwater. His prison number was 4628.

ǁkabbo was estimated as between 55 and 60 years old at the time of his arrival at Mowbray. His narrations were rich in detail, expansive, and covered topics ranging from stories of his own life to the great events and ideas of ǀxam history and literature. He contributed over 5000 pages to the archive. ǁkabbo is described by his son-in-law ǀhanǂkass’o as being ’a mantis’s man’ or a man who had mantises. It was said of his home:

Yonder place at which ǁkhabbo lived, ǁkhabbo’s place, its sorcerers will turn themselves into birds, while they wish that we might think that (they) are birds, while themselves (they) are; they have turned themselves into birds. Therefore, a sorcerer who desires to kill us, he will become for us a jackal; while he desires that we might think that (he) is a jackal.” (Diaǃkwain in LL58: 4702)

ǁkabbo was also closely associated with a sorcerer called ǀkannu (or ǀkaunu) who was the ’Rain’s man’ and known as ǁkabbo’s ’person’. Lloyd comments that ǁkabbo’s son-in-law ǀhanǂkass’o heard about the habits of sorcerers from ‘ǁkhabbo, ǃkuabba-an, ǀgui-an, ǁkuen-an, and also ǀgui-an’s mother kkebbi-an, who were all ǃgiten [sorcerers]’ (LL90: 7304). These notes associate ǁkabbo with practices involving sorcery and magic, or what is often today called shamanism.

ǁkabbo stayed at Mowbray as authority of his people’s history and cosmology and instructor of the xam language, for two years after his sentence expired in 1871. Bleek and Lloyd tried to locate his wife ǃkwabba-an (or Oud Lies) without success and had to secure his continued presence at Mowbray with the promise of a much-desired reward – a gun. Eventually, homesick, missing the company of his friends and family, and weary of living amongst “work-people who keep houses in order, and plant food”, he left Mowbray on 15 October 1873 with ǀaǃkunta for Victoria West, where he found his wife. He also wanted to visit members of his family in Calvinia and obtain news of his other relatives. ǁkabbo intended to return to Mowbray and Lucy Lloyd tried to contact him in Van Wyksvlei, but he died there on 25 January 1876. His widow ǃkwabba-an died on Charles Devenish’s farm at Van Wyksvlei the following year.

Cite: Skotnes, P. 2025. ǁkabbo. In ǃkhwe-ta ǃxōë Digital Bleek and Lloyd. Centre for Curating the Archive: https://digitalbleeklloyd.uct.ac.za/kabbo.html