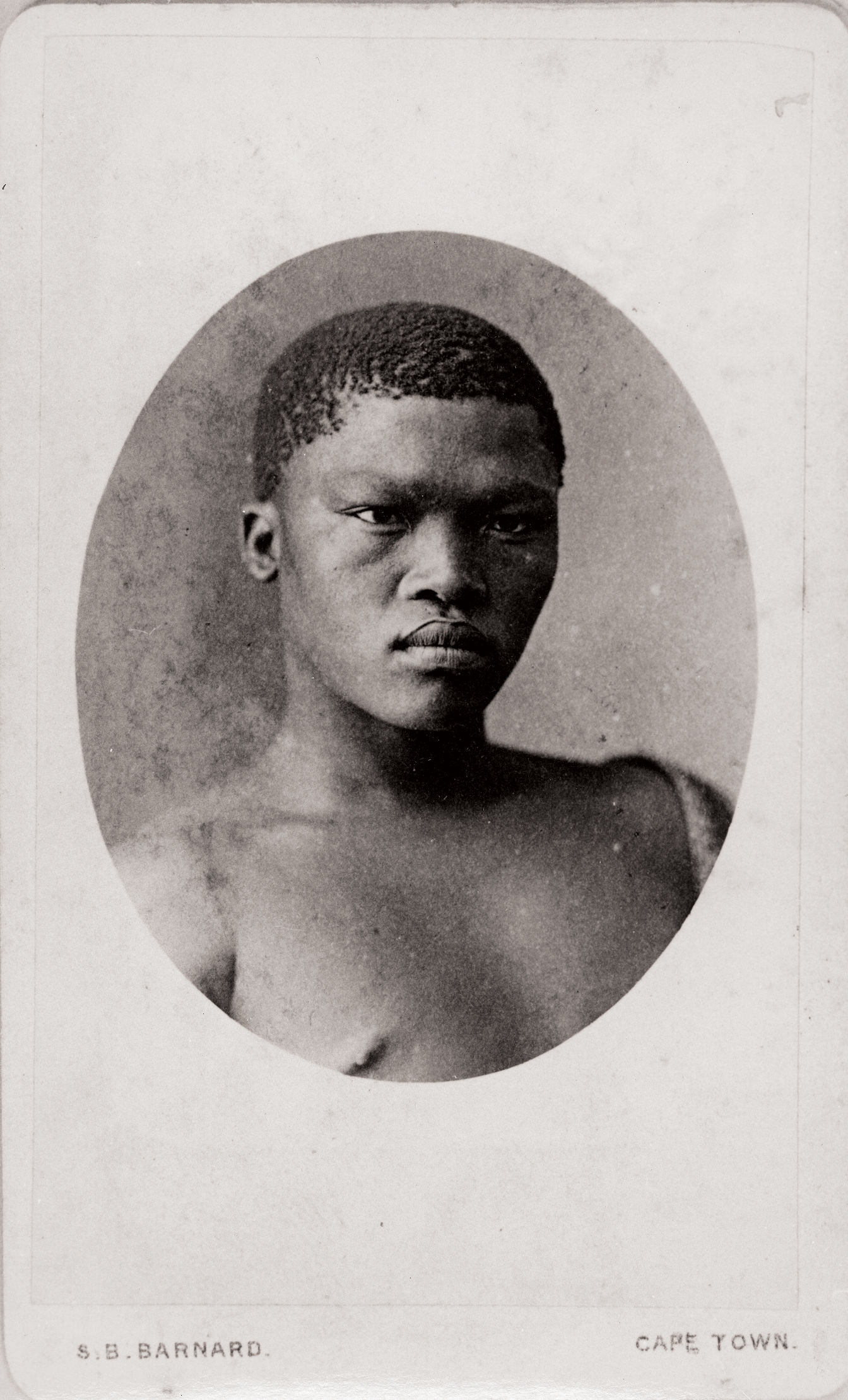

In the Breakwater prison register, ǀaǃkunta, or Klaas Stoffel, was described as a “Hottentot”, about 20 years old, just under 5 foot tall and without any religion. His prison number was 4636 and his crime was stock theft. He was serving two years with hard labour.

In fact, he was ǀxam and his home was an area called the “Strontbergen” (Strandberg), not far north of Vanwyksvlei. ǁkabbo (with whom he was arrested) called him a Ss’wa ka ǃkui, or “Flat Bushman”, meaning he belonged to a group of ǀxam who lived on the plains.

This was a place devastated by colonial incursions: the contemporary reports and letters of the magistrate for Namaqualand, Louis Anthing, detailed the atrocities of settlers and others in whose hands the fate of the ǀxam lay.

One incident described by Anthing (1863) suggests but one of the circumstances under which the ǀxam committed the crime of stock theft:

A Bushman had charge of some rams belonging to a Bastard. He ate the rams, alleging they had died from other causes. His employer told him to bring feathers in payment, which the Bushman did. The feathers were taken, but he was told they were not enough, whereupon he went home. The same day a party of six men — two Bastards, two Europeans, and two Hottentots — proceeded to the Bushman’s place of abode, with the avowed intention of killing him. They surrounded his hut during the night, and at daybreak shot him and his wife and child, leaving the bodies to be devoured by wild animals.

My informant said that he was sure the Bushman had eaten the rams, though, doubtless, from hunger, not having enough to eat.

Wilhelm Bleek had become aware of the presence of 28 ǀxam (then known as “Cape Bushmen”) at the Breakwater Convict Station and had requested that a prisoner be released into his custody for the purpose of teaching Bleek the language.

Permission was granted by the colonial governor, and the prison chaplain, the Rev. George Fisk, selected ǀaǃkunta for relocation to Bleek’s home because he was the “best-behaved Bushman boy”.

He arrived at Mowbray on 29 August 1870 and stayed until October 1873. Bleek also refers to ǀaǃkunta as a “boy” in his first report of 1873, though he was married to a woman called Ka, or Marie. They had no children. ǀaǃkunta had many relations who were also incarcerated at the Breakwater. His brother Yarrisho, or Jantje, was imprisoned with him, and Lucy Lloyd noted on the inside cover of the first of her notebooks that another of his brothers, two of his nephews, two of his uncles, and three of their sons were there as well (although she does not mention when).

ǀaǃkunta was in poor health when he arrived in Mowbray but slowly regained his strength. His initial contributions of words and sentences give insight into the inauguration of the project; observations around the home, the use of books and images to collect word lists, the enactment and even performance of actions and stories – he even sings for Lloyd -- and the use of some Cape Dutch as a medium of communication. Neither Bleek nor Lloyd knew much Dutch but the words were written phonetically (as of course) are easy to identify.

An older man, ǁkabbo, was sent to join him in Mowbray in February 1871. ǀaǃkunta’s term of penal servitude expired in mid-1871, and in his report of 1873 Bleek wrote that he had tried to establish the whereabouts of ǀaǃkunta’s and ǁkabbo’s wives in an attempt to induce them to stay longer. But they were homesick. On 22 July 1871, ǀaǃkunta told Lucy Lloyd:

“The weather is fine, I stay the two years, I go in the path, I return to my house, I return to my wife, for my wife sits waiting (for me) (in) my house, she cannot eat the springbok’s flesh, for she waits for me in my house” (WB1: 137).

ǀaǃkunta did, however, stay a further two years and left Mowbray with ǁkabbo on 15 October 1873 for Victoria West, from where they intended to go on and locate their relations and belongings. Authorities in Victoria West, conveyed the news to Bleek and Lloyd that ǀaǃkunta arrived there safely and found his wife.

Cite: Skotnes, P. 2025. ǀaǃkunta. In ǃkhwe-ta ǃxōë Digital Bleek and Lloyd. Centre for Curating the Archive: https://digitalbleeklloyd.uct.ac.za/a-kunta.html