Groot Witberg: A tentative identification of a ǀxam rainmaking place

Curated by José Manuel de Prada-Samper

I. Stories and seasons

On 29 November 1872, ǁkabbo began dictating Lucy Lloyd a kum which in the notebook bears the title ‘The Story of the Old Man who Makes Rain’ (L.II.24: 2213-2226; L.II.25: 2227-2263, see Bleek 2022: 217-224). On 11 December, after finishing this narrative, the ǀxam teacher told Lloyd ‘to leave off here, and to begin a new story about the rain man’s doings’ (2263’). The narrative that followed is in many ways similar to that of ‘The Story of the Old Man who Makes Rain’, and Lloyd may have wondered, at least initially, why ǁkabbo considered it a separate kum. This narrative bears the title ‘Rain-making (another story about it)’. Both rainmaker kukummi are among the finest told by the old ǀxam teacher and are crucial to understanding the rainmaking practices among the Upper Karoo hunter-gatherers and their connections with the hunt.

For this curation I am going to concentrate on a specific aspect of the narratives, but it is relevant to start pointing out that ǁkabbo’s request that they be considered discrete stories is fully justified. The main difference between the kukummi is both spatial and temporal. ‘The Story of the Old Man who Makes Rain’ takes place during the ǁhau or autumn period of the warm season or summer (ǁkwanna), also called ǁkwanna ǀu or ‘root of the summer’. In this first kum, the Rainmaker causes the late summer rains that bring the springbok herds back from the western part of Bushmanland. At this stage, the springbok are fat and the females bring their young with them. In our calendar, this would be late February-early March. In the second kum, we are at the beginning of the ǃkˀaua or spring period of the warm season, also called ǀkwanna ǀem or ‘stem of the summer’. More specifically, the story is set at ǃkhi:ta e, the time when the early summer rains have fallen. These rains provoke the massive migration of springbok herds from the East. At this moment of the seasonal cycle, the springbok are lean. In our calendar, this would be late August-early September (in connection with the ǀxam name for the seasons see, for example, L.II.25: 2258, 2258’, L.II.25: 2261’ and Bleek and Lloyd 1911: 314-315).

II. The mountain where the rain is made

Having clarified this, I will proceed to the true object of this curation. Well into the first narrative, ǁkabbo puts these words in the mouth of the Rainmaker:

to the mountain,

the mountain which,

I did ? cutting

above lay the rain on it.

Page 2240’ of the notebook has the following gloss to the above passage:

According to Dorothea Bleek’s Dictionary, k’’am means ‘right, not left’ while xhára could be a variant spelling of xharra, ‘to cut, make an incision’ (Bleek 1956: 119, 259). The particle ka is the possessive. As for the word ǃkau, this is a variant spelling of ǃkao, ǃkáogən, ‘mountain, stone pass, s[ynonims]. ǃkau, ǃkauoka, ǃkaugən’ (Bleek 1956: 408; cf. also 413, ǃkaugen, ǃkaukən, ‘mountain’ and 412, ǃkau, ‘stone, path, mountain’ and 444, ǃkou, ‘stone, mountain, rock’); in short, this is a generic term for a mountain or a large hill.

In the light of all this, a possible translation of the ǀxam name for this rainmaking place could be ‘the mountain of the right [in a spatial sense] cut’. This makes sense in the context of the kukummi we are discussing, since the rainmaker refers to the process of causing the rain as ‘cutting it’. For example, in the first of the narratives ǁkabbo has him saying ‘I must cutting let out the rain’s blood that the rain-blood [the liquid water] may run upon the earth’ (L.II.25: 2236-2237).

III. Visiting the Groot Witberg

ǁkabbo is vague about the location of this hill, but the scant information he provides furnishes several useful leads that may be of help to find out where it is.

The European name, Wittberg is one of them. This place name is used elsewhere in the records, in all likelihood always in connection with the same spot. In 1873 ǁkabbo told Lloyd that his brother had been killed with a ‘Kafir1 assegai’ bought at this place (Bleek and Lloyd 1911: 308). The previous year, in a gloss at the beginning of the second Rainmaker kum, ǁkabbo stated that the rain-maker ǀxaξnnu had been murdered eight years before, ‘shot … in the dark’, by his grandson, ǃkaukɘn ka ǀa:, who was ‘a “Wittberg’s man”’ (L.II.25: 2264’-2265’). These ‘Kafirs1’ who traded in weapons (very likely made of iron) and, apparently, had taken possession of the waterhole near the hill mentioned by ǁkabbo, could have been Tswana-speaking people who lived north of the Orange River.

Another lead is ǁkabbo’s observation that the Wittberg ‘It is not in Bushmanland’, and he has not seen it. I interpret this as meaning that the Wittberg is a place north of the Gariep/Orange River, that is, well outside ǀxam-ka ǃau, the territory they considered their own, but not so far as to be totally beyond their reach.

One last lead is provided by the term ǃkau which, as mentioned above, indicates that the Wittberg has to be substantial in size, unlike most of the hills familiar to ǁkabbo in the Flat Country that was his home (with the exception of the Strandberg, which is 968 metres high).

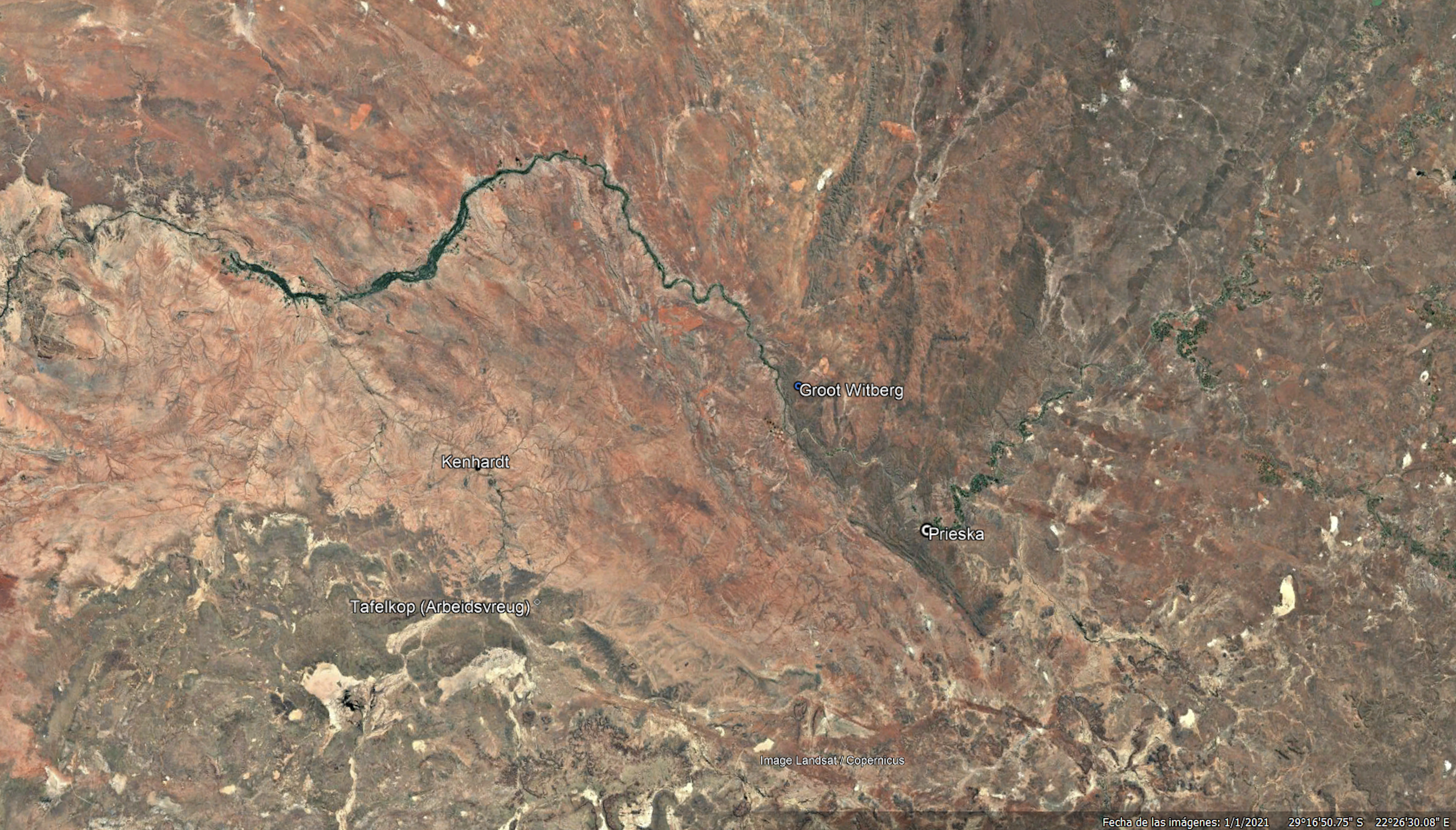

Around 2009, after carefully transcribing and annotating the two Rainmaker kukummi, I set hands to work trying to identify with the help of colonial and modern maps, as well as with Google Earth and other tools in the web, where this Wittberg could be. After ruling out several options that were within ǀxam-ka ǃau itself and did not fit ǁkabbo’s description, I considered the best candidate was a hill known in modern maps as Groot Witberg (with a single ‘t’), at 29º 10’ 00’’ S, 22º 20’ 00’’ E, about 70 km to the north-west of Prieska, beyond the Gariep/Orange river. This hill has a height of 1173 meters and is less than 7 km from the river.

Early in 2011, while I was a post-doctoral fellow at UCT’s Centre for Curating the Archive, I was granted funding to conduct fieldwork during the month of March in the former ǀxam territory. The extreme summer heat one can experience in the Karoo semi-desert made this not the best moment to travel to the area, but one of the main objectives of the trip was to document the changes in the landscape during the late-summer rains, the ǁkwanna ǀu or ‘root of the summer’ period mentioned above. Another objective was to start recording narratives from the area’s inhabitants, especially those of Khoisan descent. In addition to this, I also decided that this could perhaps be a good opportunity to make a detour across the Gariep and visit, if we could make the necessary arrangements, the Groot Witberg. Not being a driver, I enlisted the help of Neil Rusch, with whom I had visited the area in 2006, 2007 and 2009 and was also interested in the rock art and history of the former ǀxam territory. My wife, Helena Cuesta, also came along.

Rainfall was abundant that summer in the Upper Karoo, and in that we were fortunate. We were also lucky in finding very good informants in Brandvlei and environs, from whom, with the help of Neil as interpreter, I recorded oral narratives that, in some cases, were variants of those recorded by Bleek and Lloyd in the 1870s (see De Prada-Samper 2025: 226-243, De Prada-Samper 2016). We left Brandvlei on 8 March and that evening we arrived at the farm Arbeidsvreug, south of Kenhardt, in the heart of ǁkabbo’s territory, where we intended to spend several days. At Arbeidsvreug we enjoyed once again the hospitality of Nak and Alma Reichert who, when told that we were interested in visiting the Groot Witberg, north of the river, very kindly contacted on our behalf the owners of the farm where the hill is and made with them the necessary arrangements for our visit.

We crossed the river and reached the area where the Groot Witberg is on 15 March. Once on the farm, Mr Ernie Vivier had the kindness of guiding us to the Groot Witberg. Before that, he told us that the hill had a permanent waterhole, and that close by were the remains of what he called ‘a Griqua settlement’. Mr Vivier also said that the area had recently been the subject of a land claim that, if we understood well, had been successful, although the claimants had preferred to receive cash compensation rather than regaining possession of the land. Unfortunately, we did not ask who these claimants were.

We ascended the hill, which is indeed massive, and reached the top. The view of the surrounding area was spectacular, and one could well imagine a rainmaker standing there and feeling in control of the rain. We were lucky to witness how a spectacular cumulonimbus calvus discharged rain on the horizon. We eventually found the waterhole Mr. Vivier had mentioned; at that time it was of modest proportions and frequented by bees from a beehive nearby. Not far from the waterhole we spotted a small scatter of tools and small quartz pebbles. The source of the latter may have been the reddish rock with quartz veins that abounded in the hill. The presence of quartz may be relevant to identifying this Witberg with the one mentioned by ǁkabbo, since the ǀxam associated it with rain.

IV. Is the Groot Witberg K’’am xhara ka ǃkau?

To conclude, are K’’am xhara ka ǃkau and the Groot Witberg the same place? The identification of the ‘mountain’ mentioned by ǁkabbo with the hill we visited in March 2011 is indeed plausible. The hill is massive and is only 117 kilometres from ǁkabbo’s territory. It has a permanent waterhole, and from the top the progress of the rain clouds is very visible. The ‘Griqua settlement’ pointed to us by Mr Vivier could have originally been inhabited by the Bantu-speakers ǁkabbo mentions.

The hill is in a landscape very different from the one that was familiar to him, blessed with more abundant rainfall. The area on which it stands is part of the Ghaap plateau, and the vegetation is savanna. The people who called this territory their home were, in all likelihood, ancestors of the present-day ǂkhomani, whose language is close to ǀxam. Yet if ǁkabbo’s Rainmaker ‘cut’ the rain in this hill, and ǀaǃkuŋta had been there, this must have been a place where people from both sides of the Gariep/Orange River interacted. It surely was also a place where one had to tread with care, as the presence, perhaps permanent, of the Bantu-speakers who traded in deadly iron weapons would have made it dangerous for the hunter-gatherers

Of course, this is just a preliminary report. More visits to the area and more historical research are needed to determine if the K’’am xhara ka ǃkau and the Groot Witberg are one and the same place.

Language disclaimer

Some terms and expressions quoted in this curation are taken directly from the archival documents. They may include racist or otherwise offensive language and ideas. Their presence here reflects the historical record; it does not imply endorsement or agreement.

Sources

- Bleek, D. F. 1956. A Bushman Dictionary. New Haven: American Oriental Society.

- Bleek, D. F. and Jeremy Hollmann (ed.). 2022. Customs and Beliefs of the ǀxam. Johannesburgh: Wits University Press.

- Bleek, W. H. I. and Lucy Lloyd. 1911. Specimens of Bushman Folklore. London: George Allen.

- De Prada-Samper, José Manuel. 2016. The man who cursed the wind. Die man wat die wind vervloek het. Cape Town: African Sun Press.

- De Prada-Samper, JM. 2025. Fading Footprints: In Search of South Africa’s First People. Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball Publishers.

- Hampson, Jamie. The Materiality of Rock Art and Quartz: a Case Study from Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 23: p 363 - 372.

- Stow, George and D. F. Bleek. 1930. Rock Paintings in South Africa. London: Methuen.