“Candid outpourings”:

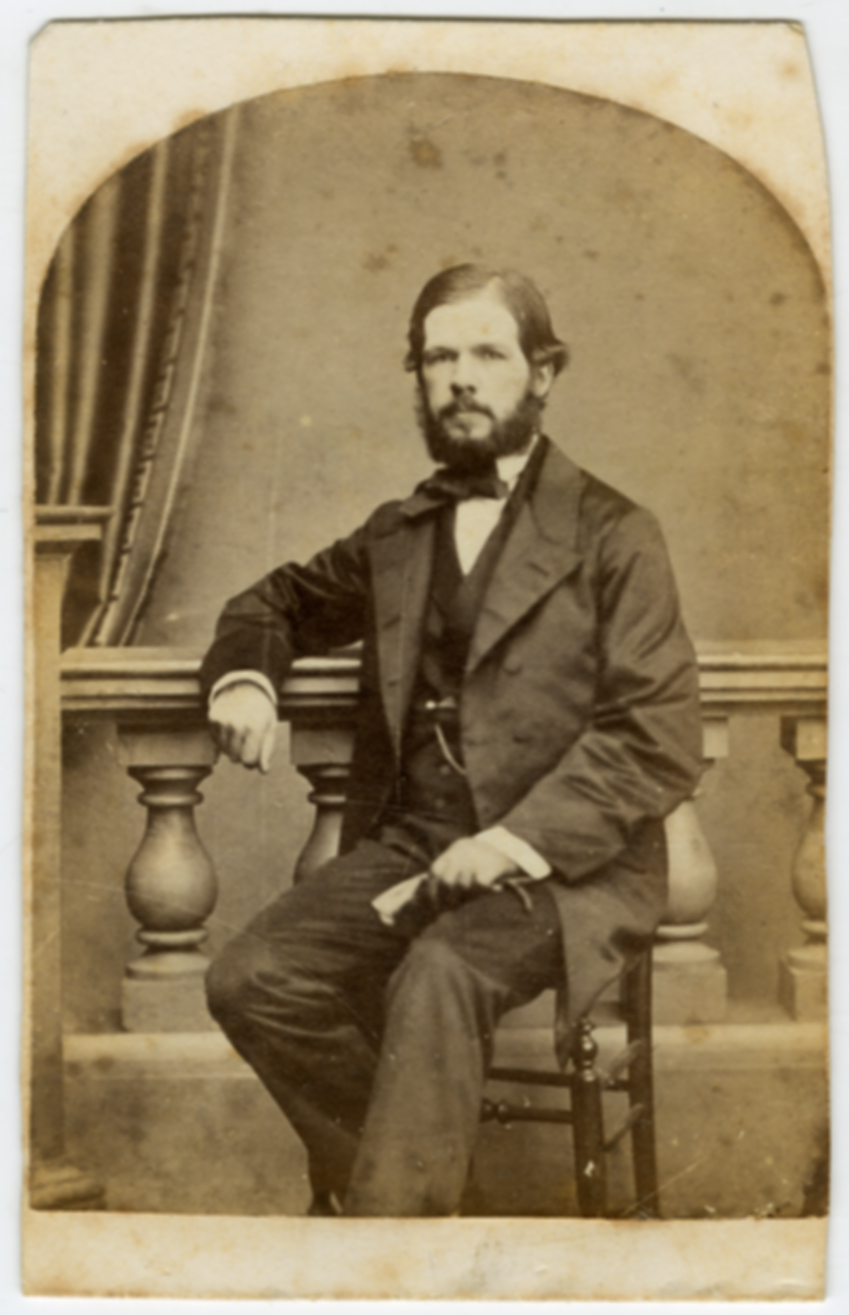

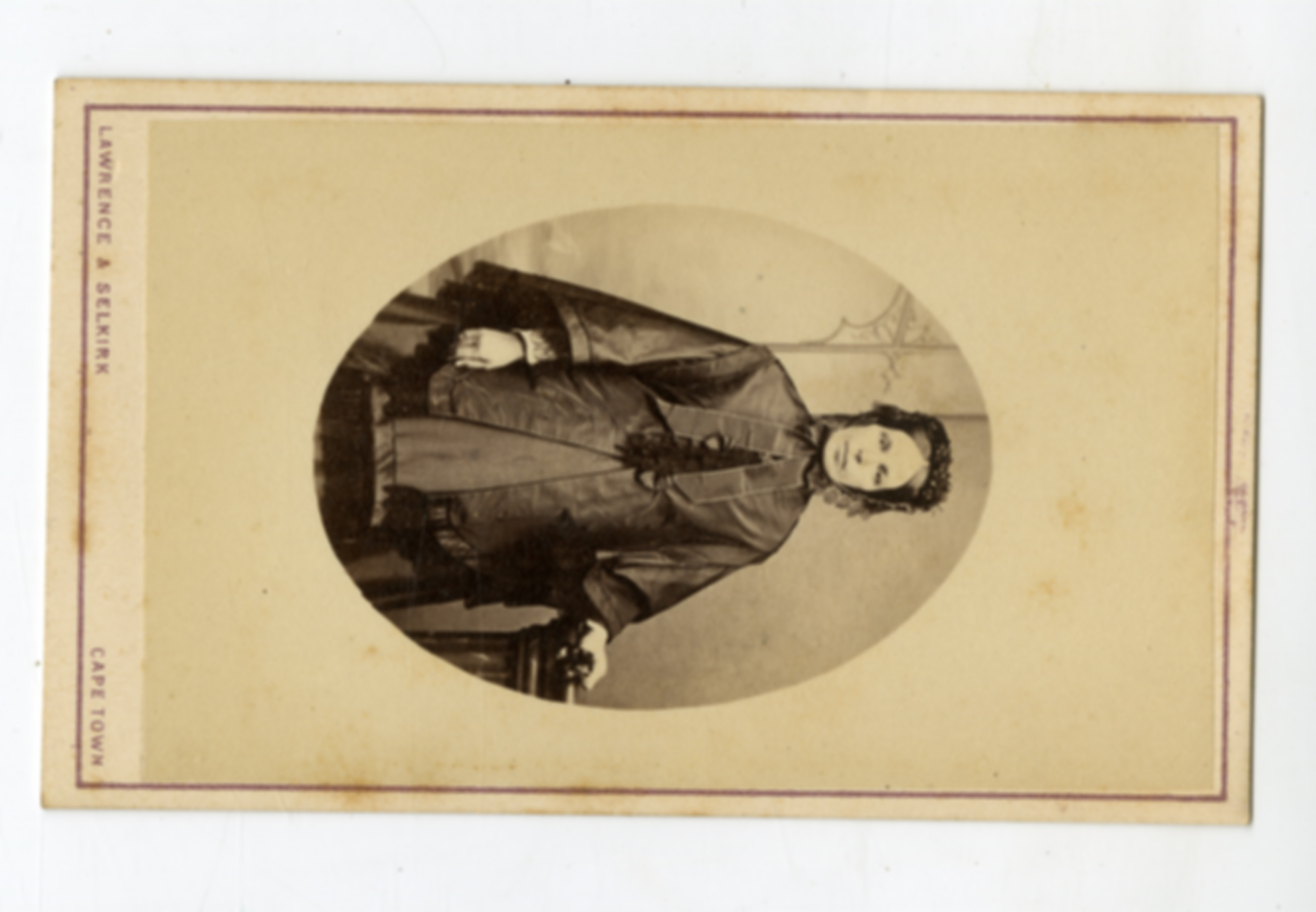

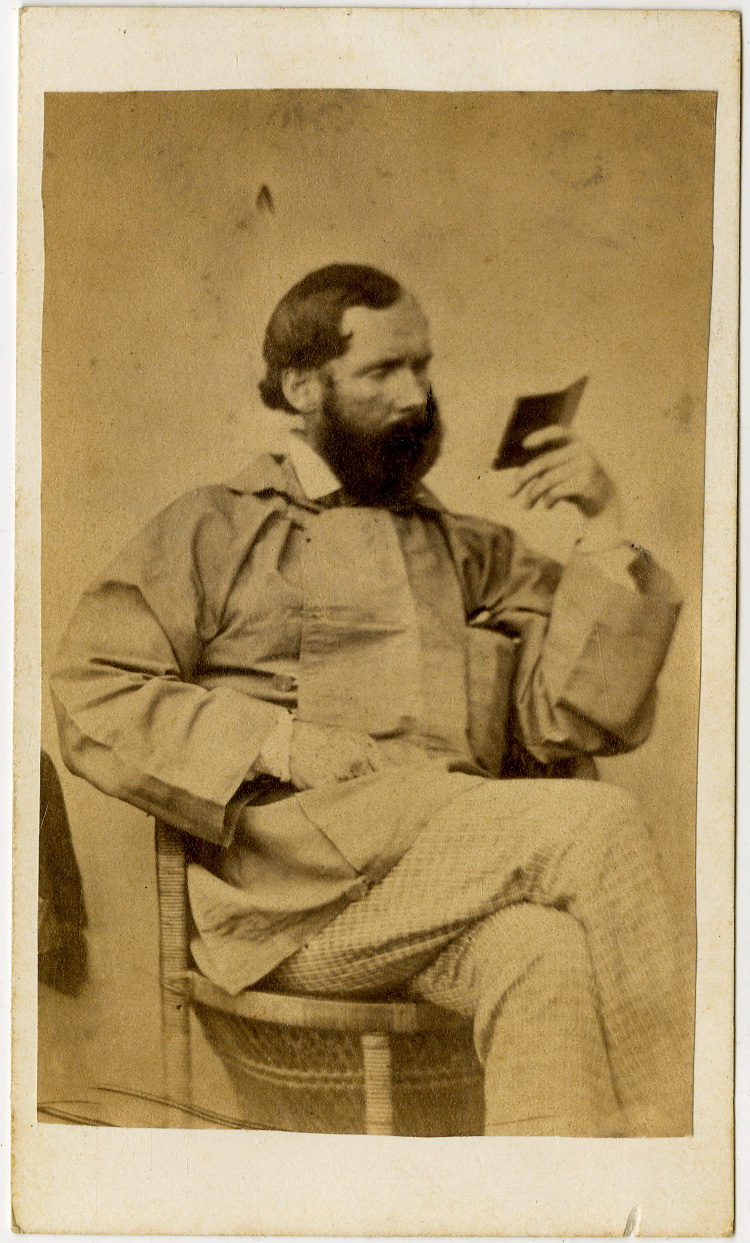

The main characters in Wilhelm Bleek and Jemima Lloyd’s intimate correspondence, 1861-2.

Curated by Eustacia Riley

The Bleek and Lloyd correspondence collection is at the foundation of the “Bushman researches” of Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd. The almost unbelievably unusual research environment that sprang up in a genteelly impoverished colonial household of the 1870s and 80s Cape did so at least partly out of the written exchanges between its major researchers.

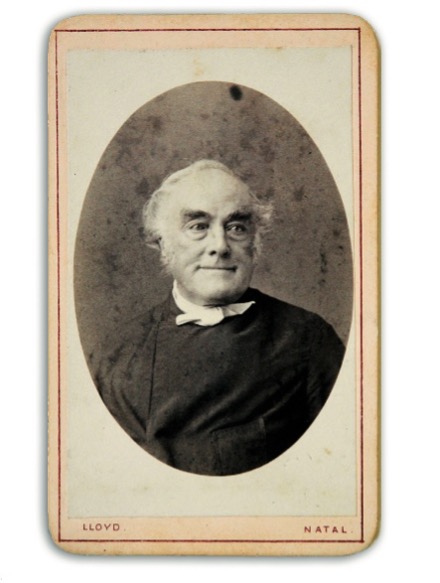

For scholars, frustrated by the relative dearth of personal information about the chief researchers, the most informative sources are the “distant courtship” letters exchanged between Jemima Lloyd and Wilhelm Bleek before their marriage – arguably an event without which the Bleek and Lloyd archive wouldn’t exist. They reveal the characters of those behind the work and hint at some of their motivations for doing it. For instance, Wilhelm Bleek’s letters to Jemima Lloyd are not merely love letters: they also reveal his “inner man”; his philosophies and beliefs, ideas and intellectual rigor; his curiosity applied to almost any subject – for example his religious discussions with Jemima in response to her many “puzzles” (a feature of their earlier letters), probing the “great original ideas”. While focused on Christianity in this instance, Wilhelm’s investigation of other great, original ideas guides much of his philological research too. It is also clear, early on, that Jemima wholeheartedly valued and encouraged Wilhelm’s intellectual spirit and philosophy – which also explains her dedication to completing and publishing his life’s work after his death.

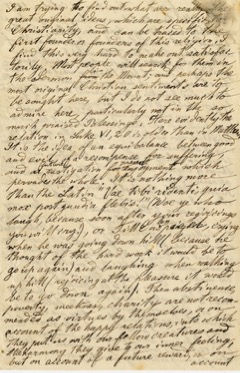

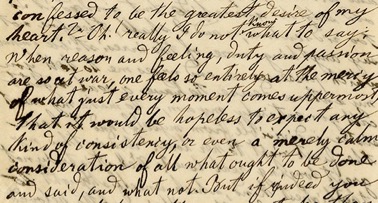

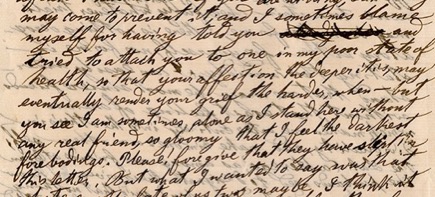

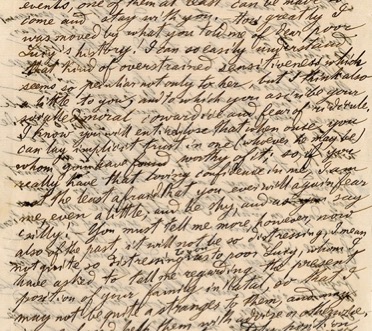

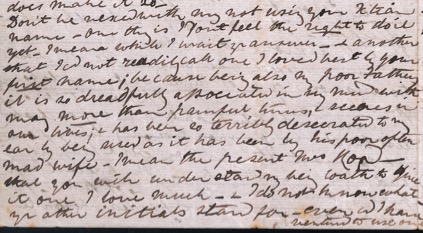

This is not to say these are not love letters: they document Wilhelm and Jemima’s courtship and reveal their rawest feelings. In his proposal letter of 31 October 1861, for instance, Wilhelm reveals his “selfish yearning” for Jemima; how “reason and feeling, duty and passion” are at “at war” within him. He refers to this internal “battle” and his "desperate" struggle over the course of several subsequent letters [See C4.10].

Ill health probably lies at the root of Wilhelm’s emotional tumult in these letters. Even his declaration of love – with the prospect of “heavenly bliss” and the “greatest desire” of his “starving” heart – is undermined by his fear of shackling Jemima to a “sour old selfish invalide” with limited prospects; as such he characterizes his proposal, and his desire to marry Jemima, as almost “too ridiculous” to contemplate.

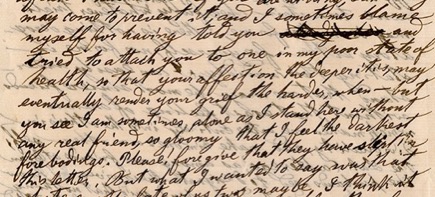

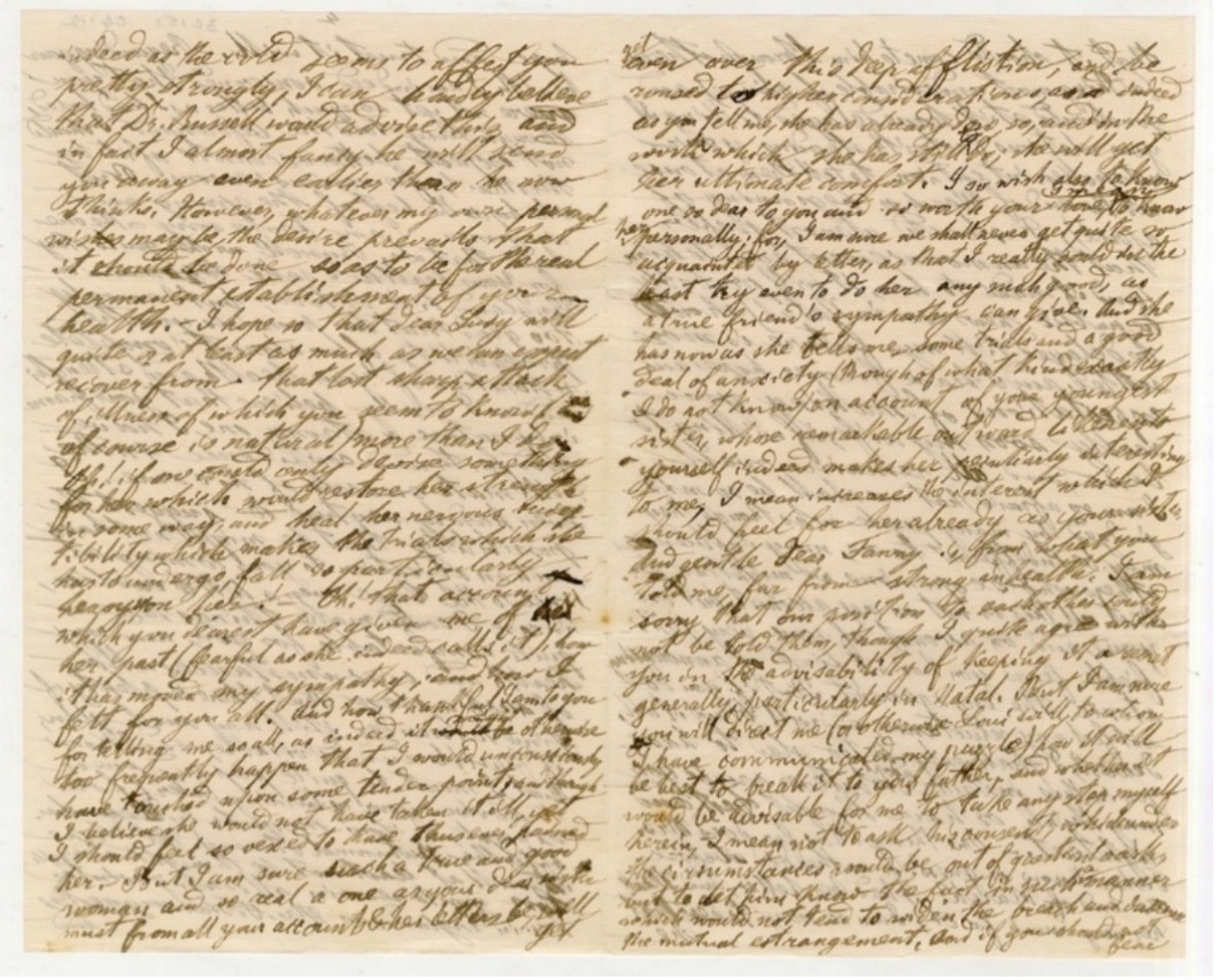

Illness is also inseparable from loneliness and isolation in Wilhelm’s letter to Jemima of 19 February 1862, written shortly after the proposal letter. Wilhelm clearly craves a wife, family and home after a long period of invalidism and distance from his loved ones and friends in Europe. He had been living in lodgings since moving to the Cape from Natal in 1856 to work as Sir George Grey's official interpreter and catalogue his private library. Wilhelm tells Jemima that he stands alone in the Cape “without any real friends” – an unmarried German intellectual who doesn’t “go at all into society” [C4.18]. (probably because he eschews the “conventionalism” of “English prudery”) [C4.12]. Once engaged, he encourages Jemima to come to him as soon as possible (health permitting) so they may create a “comfortable home” together – his longing overcoming his prudence and deep reservations (or “darkest forebodings”) about “attaching” her to one as ill as he is [C4.10]. Throughout their courtship, both Jemima and Wilhelm are intent on “doing” and “acting rightly” – Jemima’s doubts and Wilhelm’s reservations are very much part of their moral code.

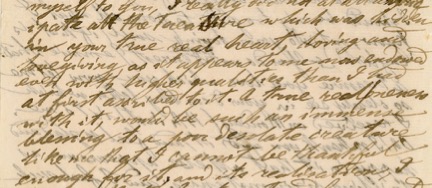

Another feature of their attraction is their openness, a dedication to telling each other “all”. This insistence upon honesty is shared alongside idealism, especially with regard to the finer feelings, and the letters contain much discussion of “oneness” as the “highest” form of love and the ideal of marriage. Both believe that the "candid outpourings” of each other’s hearts allow them to truly understand each other and be almost of one mind – what Wilhelm describes as the "exact feeling of oneness" that allows you to "enter entirely into the other's individuality, and make him one's own other" [C4.10].

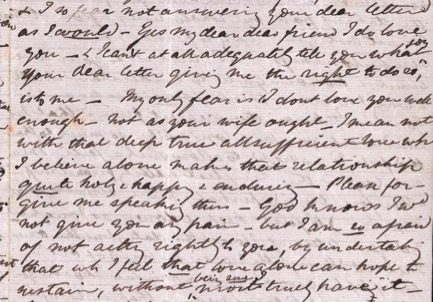

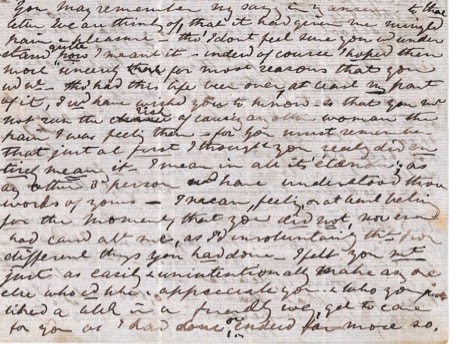

That said, understanding and one-mindedness were not immediate for the couple. While Jemima is definitely in love and never in any real doubt of her feelings, she responds to Wilhelm’s proposal letter by writing that she cannot be sure she possesses the necessary “allsufficient love” needed to be his wife. This slightly tepid reaction is largely Wilhelm’s fault. His proposal outlines all of his doubts regarding the wisdom of their union as well as an overuse of the terms “brotherly” and “sisterly” – so naturally she misunderstands his true feelings and intentions.

Unfortunately, Wilhelm and Jemima are both guilty of over-thinking and over-explaining their feelings – almost resulting in the derailing of their engagement. Jemima’s explanation and discussion of the proposal misunderstanding takes up a goodly portion of her following letters, drawing equally muddled explanations from Wilhelm. It is a near-miracle they managed to understand each other’s true feelings and end up together in Cape Town.

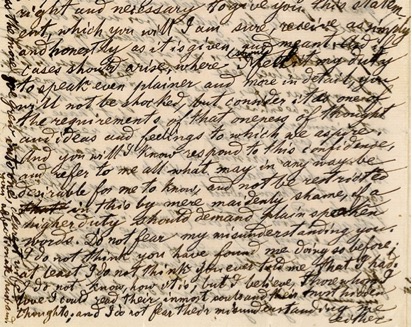

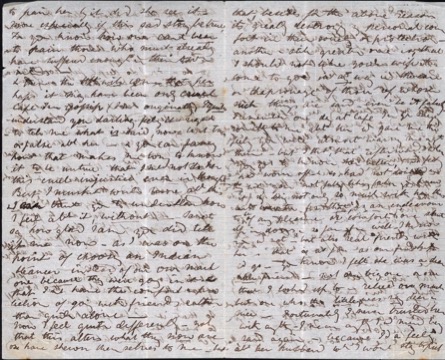

Nowhere is the willingness to share all more evident than in Wilhelm’s letter to Jemima, dated 28 April 1862, regarding their mutual “fitness” for the “married state” – whether they can safely engage in the sexual act as invalids – and reminding her, because she has no mother to tell her these things, of the physical consequences of marriage and children. He makes a plea for her to trust and confide in him as if she were already his wife and embrace these “realities” without shock as they are natural, almost holy acts, necessary for the continuation of the species. Wilhelm sets up an expectation of plain, honest speech for their upcoming union, which he frames as a requirement of the “oneness of thought and ideas and feelings” to which they both aspire. Wilhelm assures Jemima that he is able to read the “inmost souls” and “most hidden thoughts” of those he loves – so Jemima must fear no misunderstanding if she confides in him and must not feel “restricted” in any way [C4.14].

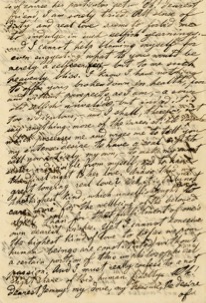

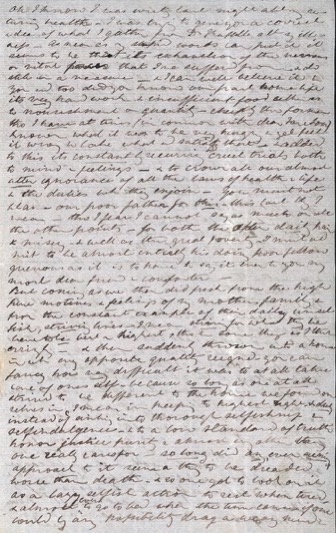

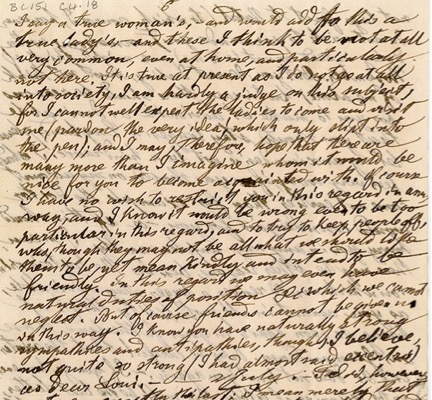

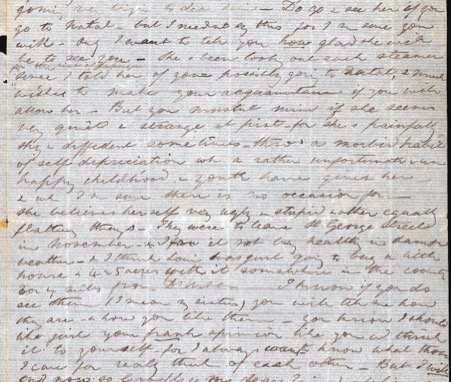

In addition to sharing their innermost thoughts and feelings, Jemima and Wilhelm both demonstrate critical, forthright and often high-minded tendencies. Jemima admits to causing shock and offense when she is “compelled” to challenge the “bigoted” views held by her religious friends and relations in England and “give my doubts an airing” [C8.7]. For Jemima her doubts are inseparable from her principles, and she has strong feelings about things – described by Wilhelm as “strong sympathies and antipathies” [C4.18]. When she feels “caged”, unable to engage in these discussions for fear of “paining” the people she loves, Jemima judges herself to be dishonest and a “moral coward” [C8.9]. She goes so far as describing the dreaded Natal as a place where she can be free – “where even a coward can be free” – from the restrictions of polite, orthodox English society [C8.6].

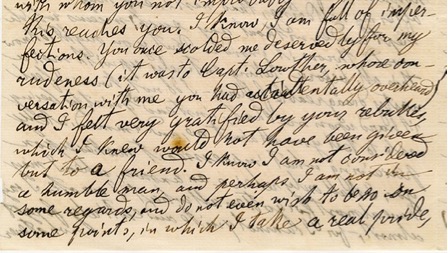

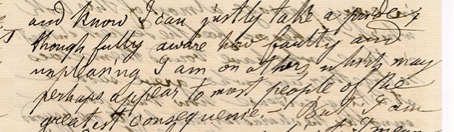

Wilhelm is not overly concerned with being considered “unpleasing” on points others may find of the “greatest consequence”. He confesses he is not considered a “humble man”, nor does he wish to be as he takes “a real pride” in “some points” [C4.12]. He also acknowledges his “faulty” character, “full of imperfections”, even expressing gratitude for Jemima’s rebuke at Mrs Roesch’s when she scolded him for being rude to Captain Lowther, also staying there.

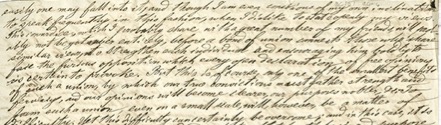

Crucially, Jemima and Wilhelm enjoy a “meeting of the minds” – ignited at Mrs Roesch’s dinner table and stoked throughout their exchange of courtship letters. In his first letter to Jemima after their meeting, dated 15 May 1861, Wilhelm describes how his sisters think him a "wicked unbeliever" due to his unorthodox religious views, leading him to appreciate her all the more since he is able to engage in this kind of open discussion with her. He also admits to “cowardice”: his “dislike to state openly” his views; how he may not entirely get over this cowardice/reluctance until he finds the “bond of union” connecting those with similar views; a union that would strengthen and encourage him boldly to face the "furious opposition" which declaring "free opinions" is certain to provoke. He outlines the benefits of such a union by which “our true convictions must gather strength and fervency, and our opinions will become clearer, our purposes nobler…”, but admits how difficult it is to find someone to form one with. While Wilhelm is writing about religion here, he is clearly also appealing to Jemima to “unite” on the basis of their shared convictions and noble aspirations [C4.1].

Another notable feature of these letters is their authors’ acknowledgement of their psychological struggles. They are peppered with references to “internal battles”, doubts, “moods”, and sensitivities – from Wilhelm’s dark, “gloomy” thoughts to Jemima’s detailed descriptions of her and Lucy’s “morbid thoughts” and nervous afflictions.

Wilhelm points out Jemima’s “despairing, moody” sentiments in her letters, but he promises he isn’t deterred by them. He understands them once she is “part of him” and he is able to feel the “impressions of her mind” [C4.18]. Jemima reassures Wilhelm that the Lloyd sisters favour their mother’s family, stressing their sane and sensible nature despite their trials and associated afflictions: “I think it could be difficult to find a more thoroughly sane set of sober minded people” [C8.9].

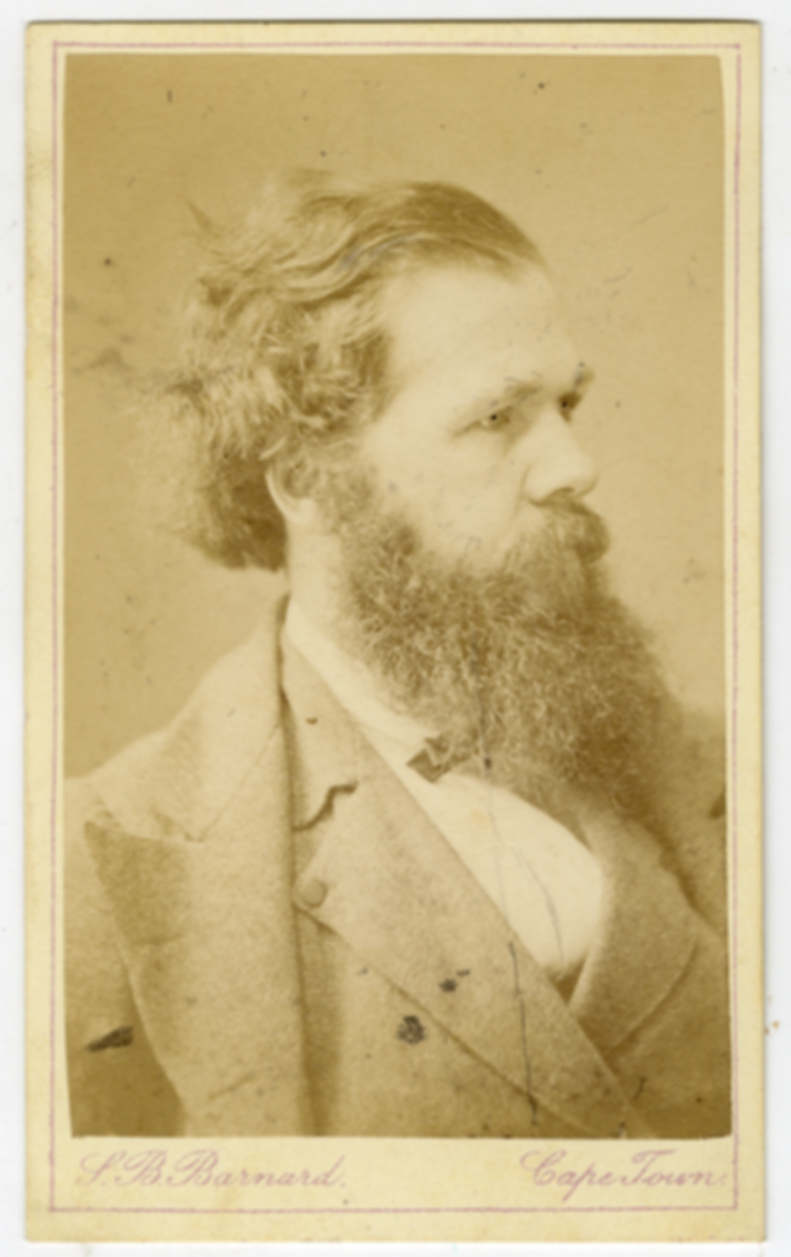

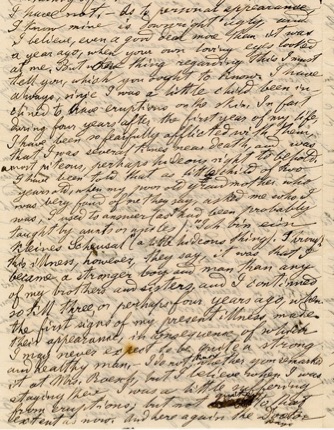

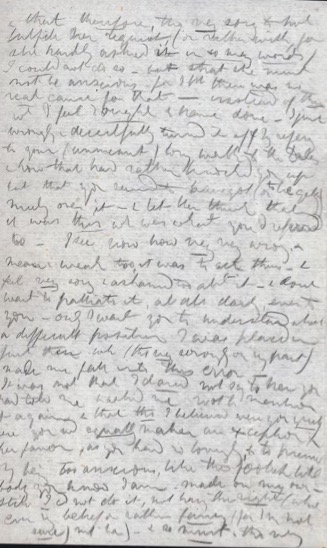

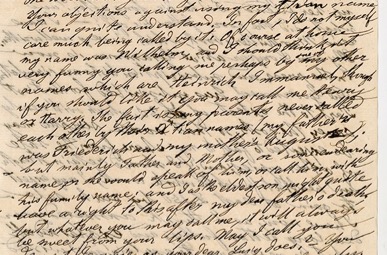

Wilhelm’s brutally honest descriptions of himself in his courtship letters are tied to his unselfish concern for Jemima; his “selfish” joy always in tension with what he believes is best for her (he even compares being married to an invalid as a kind of slavery) [C4.8]. In a memorable letter of 9 April 1862 he writes that in terms of “personal appearance” he knows he is “downright ugly”, a self-perception borne out by his eruptions and loss of teeth but probably also learned from his aunt’s and uncle’s cruel jokes about “a little hideous thing” when he was a sickly child. He paints himself as an almost-pitiful man, undeserving of a wife’s love, by describing what Jemima may expect in terms of his physical frailties and character flaws and stressing what a blessing the love of a “true real heart” and “true real oneness” would be to “a poor desolate creature” like him [C4.12].

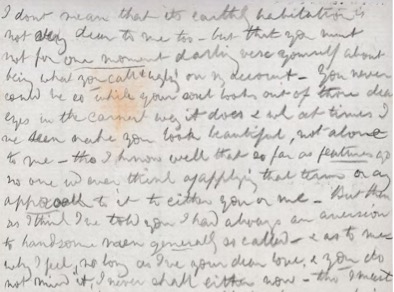

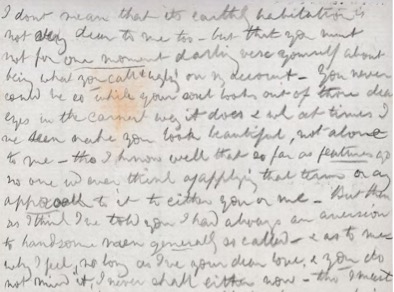

Jemima rightly objects to Wilhelm’s description of himself as “ugly”, describing how when she first saw him, she was struck by his face and its character when he sat down late at their dinner table at Mrs Roesch’s. She assures him she is not flattering him with “absurd compliments” as there will be “none such from me” – and, delivering a very backhanded compliment, proclaims that she has never seen a “handsome man I could abide” [C8.14]. A few months later she insists that Wilhelm mustn’t get false teeth on her account as it is who he is/how his soul is, not how he looks, that matters to her. Again, she writes that he mustn’t call himself “ugly” as he could never be so to her and that his soul is beautiful. She then ruins this sensitive moment by observing that no-one would call either of them beautiful and reminding him she doesn’t like handsome men [C8.19]. In the following letter she reprimands him for writing that he is “even plainer than when I saw you last” and encourages him to see himself as others see him: the effects of happiness and hope having altered his face as it has hers [C8.20].

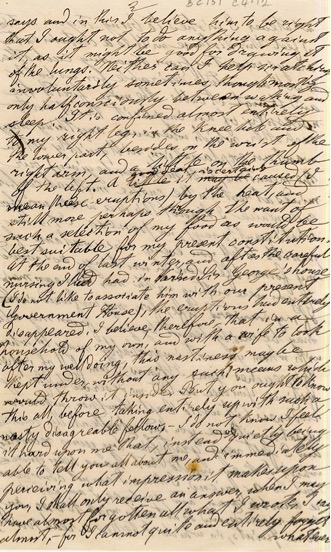

Along with his physical imperfections, Wilhelm fears never quite recovering his health and worries he did not make that clear enough in earlier letters to Jemima before his proposal. But he resolves not to dwell too much on these dark thoughts as they make him say “savage things” [C4.8].

Wilhelm’s description of himself in savage terms is linked to his constant emphasis on the need for “implicit trust” between them, allowing for “mutual confidence” so that they are able to freely share what they “ought to know” about each other before marrying. This is especially evident in the “married state” letter of 28 April 1862, where he asks Jemima to put aside any “mere maidenly shame” and inform him of anything she thinks he should know before or during their marriage – because “higher duty” of the married state demands “plain spoken words” [C4.14].

As much as Wilhelm wants to know about Jemima, he also wants to tell her “all about” him – how she will be “taking entirely up with such a nasty disagreeable fellow” – before she gives him her final answer to his proposal [C4.12]. While fearful of ever recovering completely, Wilhelm isn’t altogether hopeless regarding his condition: he is optimistic that with a wife’s loving care and a home of his own, as well as decent meals suited to his constitution, his physical “nastiness” may be suppressed or even disappear completely.

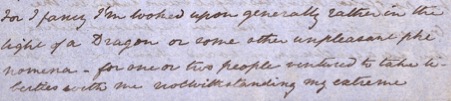

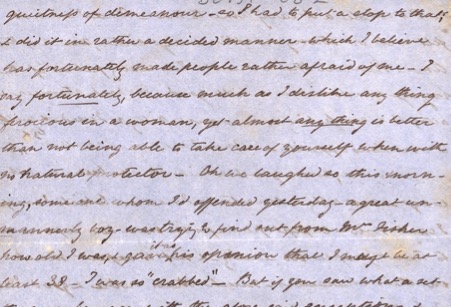

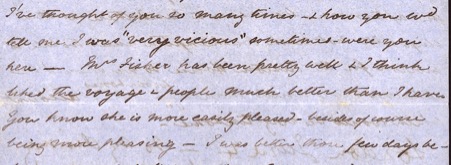

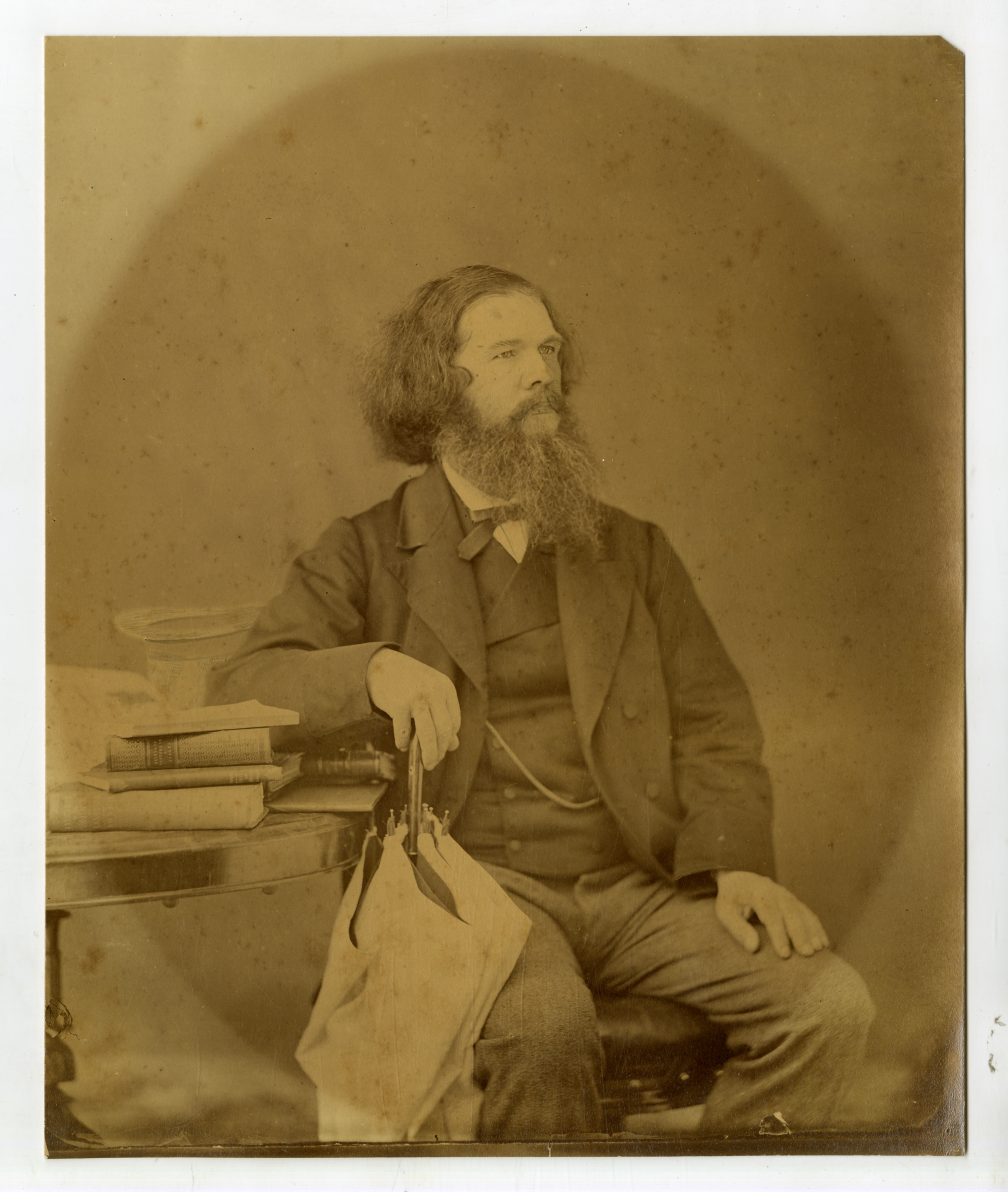

In a similar spirit of honesty and self-deprecation, in only her second letter to Wilhelm after their meeting, Jemima paints a rather forbidding picture of herself, writing of being perceived as a “dragon”, as considerably older than she really is, of not liking people or the voyage as much as Mrs Fisher does, or being as “easily pleased” or “pleasing” as she is, in her account of her voyage to England on “The Celt” in May-June 1861 [C8.2]. In an April 1862 letter Jemima describes herself as overly critical, “almost too apt I am to pick peoples minds and characters unmercifully to pieces” and then be disappointed, forgetting human faults in others and herself [C8.17]. Like Wilhelm, Jemima is reluctant to behave in a manner that pleases others if it goes against her principles.

One imagines a great deal of Jemima’s no-nonsense persona, independence and “decided manner” are rooted in the unusual circumstances of her unprotected life with Lucy after their expulsion from their father’s home. As women alone, and after Lucy’s experience with public opinion, scandal and Natal gossip after her broken engagement with George Woolley, Jemima is naturally concerned with her reputation, and in the May 1861 letter she is signalling to Wilhelm that she is “able to take care of herself”– although she imagines him calling her “very vicious” if he were there. (In this instance her viciousness takes the form of cutting young men down if they take liberties with her, misled by her extremely quiet demeanour). In a much later letter she explains, in a not entirely enthusiastic response to Wilhelm’s less than unequivocal proposal, that after witnessing others’ “suffering” she resolved “never to give my love where unreturned and therefore unwanted” [C8.13].

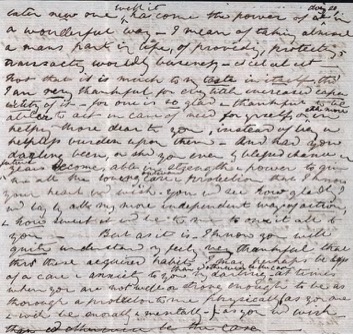

In a detailed account of her – and Lucy’s – “sad history” in Natal, Jemima describes how the elder Lloyd “brothers” were forced to embrace their “power” and independence, “almost take a man’s part”, in order to protect, provide and care for themselves and their “poor little ones” amidst “cruel trials both to mind and feelings” [C8.15, C8.17]. Jemima does assure Wilhelm that while she will “gladly…lay by all” her “more independent ways of action” once married to him – if he is strong enough to care for and protect her – she is sure having a wife with such “habits” will also lessen his burden of care and anxiety [C8.17].

Jemima is extremely modest regarding her appearance as well as her higher faculties. Before meeting Wilhelm, she writes, feeling “so weak and erring and so wanting in highest beauty both of body and mind; as I felt myself to be”, that any man she felt she “could truly look up to and entirely love” wouldn’t care for her in return. Like Wilhelm, Jemima describes herself as “ugly”, sometimes even in the most optimistic contexts. In a discussion of her photograph, taken in Bonn to send to her intended, she writes that lately she hasn’t recognised the happy face she saw accidentally in her mirror as “it seemed so unlike the ugly (at times very ugly) one she used to see there” [C8.20]. She also refers to herself as being “plain”; how “in past years it has been even painful to me to be so far from that real beauty wh I think one so longs to see in women. But then I know for one thing that I was even far plainer then than now.” Fortunately, Jemima has lately come to believe that it is the “inner self” of the other that people are drawn to and not their faces or their soul’s “earthly habitation” – so that even a plain face is “beautiful and pleasant to the eyes of those who love it” [C8.19].

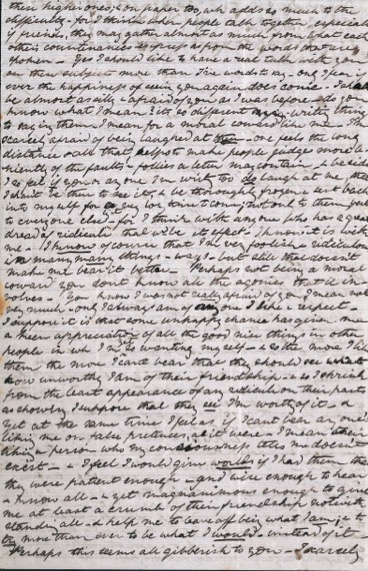

Jemima also feels intellectually insecure in comparison with Wilhelm, dreading the ridicule of one she respects so highly and fearing he will laugh at her “crude ideas or awkward ways, or stupid expressions” [C8.14]. This insecurity isn’t unique to Wilhelm though: Jemima describes her “agonies” over feelings of unworthiness even in the company of good friends and her terror of people she likes and respects discovering just how “foolish and ridiculous” and wanting in “good, nice things” she really is [C8.9].

It isn’t clear whether Jemima was ever really the subject of Wilhelm’s ridicule. He does refer to being known as an "inveterate teaser" [C4.11]. but whether he has “teased” her in person or not, Jemima still “fears” his sarcasm and ridicule [C8.14]. Wilhelm, in turn, is concerned that Jemima has told her sisters that he sometimes laughs at people and has thus given them a poor impression of him [C4.9]. He reassures Jemima that when she is comfortably his wife, with trust and "loving confidence" in him, she will never again fear him or feel shy or "silly" around him [C4.10].

Despite her humility and numerous other sympathetic qualities, Jemima can be hard to like in some of her courtship letters, sometimes coming across as priggish and opinionated, overly concerned with other people’s “depth” and whether or not they are worthy of her respect or friendship. It is also hard not to view her constant allusions to her weakness, poorliness, incoherence and exhaustion in the letters as, at best, psychosomatic and, at worst, hypochondria.

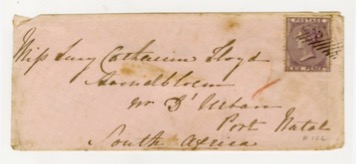

Jemima is sensitive to her and Wilhelm’s social standing in the colony. In a letter written shortly before sailing to the Cape, Jemima debates travelling with her dear friend Mrs. Hill because she has heard a “shocking” rumour about her. Although she admits the rumour may just be “cruel Cape” gossip, Jemima fears travelling under the Hills’ protection will tarnish her and Wilhelm’s reputation – she doesn’t want Wilhelm’s wife to arrive in the “chapronage” of those of whom such things are said, even falsely, and her comfort in the Hills’ “society and protection” has been destroyed. Although she will avoid the temptation to put on “airs”, she admits that Mrs Hill has “Cape ways of thought and speech”; that she’d be “pained” to interact with her now and doesn’t want to further upset the poor woman by acting “differently”. She then backtracks on how close she and Mrs Hill are, writing that she felt the woman was a “dear little friend” – not a “big” one or one she “looked up to” but who, although “little”, was still “very dear and nice”. Jemima expresses relief that the Hills will probably sail on the 15th so she’ll only meet them again when she is “safely” with Wilhelm in Cape Town [C8.22].

Wilhelm and Jemima are certainly not above indulging in “gossip” – at the very least they always update each other on the endless comings and goings of people they know on the Mail steamer, or what they have heard in letters – despite commenting negatively on its ill effects and fearing it in relation to their own lives and engagement. Like Jemima, Wilhelm is attuned to delicate social considerations: in a letter discussing ladies and Cape society in the light of future potential friends for Jemima he reminds her that, when a couple, they will have “natural duties of position” that must not be neglected. Despite Jemima having strong sympathies and antipathies, in making friends she mustn’t be too “particular” and mustn’t “try to keep people off”, even if the person “may not be all what we would like them to be” but are nonetheless friendly and “mean kindly” [C4.18].

Jemima readily admits that she is sometimes oversensitive and mistaken in her judgements. In an April 1862 letter she worries she may have misled Wilhelm, giving him the wrong idea about her mother’s family by telling him things which turned out to be untrue, due to her being oversensitive and having “mistaken notions of things” [C8.18]. It seems this finely tuned sensitivity is a feature of the Lloyd sisters though (and the vagaries of letter-writing) – on another occasion Jemima tells Wilhelm of a misunderstanding with her maternal Aunt Julia Byron. On her visit she realises that the pain felt by the sisters due to their aunt’s “cold” letters were in fact a result of her not understanding that their silence and “sad, cold” letters” were due to their writing in sorrowful times. The Lloyd sisters had refrained from telling their aunt’s family of their sorrows to avoid causing pain, which the Byrons interpreted as a lack of caring. Jemima assures Wilhelm that the matter is now resolved [C8.8].

One of Wilhelm’s earliest and most fervent wishes is for Jemima to visit his dear “mutter” in Bonn so they may get to know, and love, one another. Luckily Jemima is keen to gain a mother’s love, having lost her own at a young age, and arrangements are made. But the visit is not all smooth sailing. Partly due to the language barrier, and partly due to Jemima’s commitment to her “wife’s duty”, Jemima inadvertently commits what she terms an “error” and “wrongdoing” by refusing to reveal to Auguste how Wilhelm was injured in “an accident” at his lodgings. Despite sharing most things with his mother, hitherto Wilhelm’s “first friend”, in this instance Wilhelm is careful to avoid worrying his mother, who is especially anxious about his health. Jemima takes her responsibility for the confidences of her prospective husband very seriously and is willing to endure the discomfort from this “misunderstanding” (she has a similar issue soon after by refusing to tell Wilhelm’s family doctor about the accident). Luckily, the misunderstanding is soon “mended” after Jemima explains her reluctance to share Wilhelm’s condition to Auguste, who is predisposed to being on good terms with her son’s intended. Jemima tells Wilhelm that she is sure that his mother, due to her great love for him, does love her “a little”. But she longs for that “belong-to-ness” feeling with his mother and trusts it will come one day [C8.20].

A more amusing instance where Jemima has mistaken notions due to her oversensitivity occurs when she asks Wilhelm if she may call him by another first name – his reminds her too painfully of her father, William Lloyd [C8.10]. Wilhelm agrees (some options are discussed and vetoed; she tries out “Heinrich”), but hopes once she hears his name spoken lovingly by his family in Bonn, she will change her mind about using it, which she thankfully does.

Fortunately, Jemima’s liberal and questioning spirit, and unselfish care for her loved ones eclipses the less likeable aspects of her personality. Indeed, one of the most appealing features of Jemima’s character is her devotion to Wilhelm, evident early on in their courtship when she saw his “soul” looking out from his “dear eyes” and continued with her nursing him through his illnesses and eventual death [C8.19].

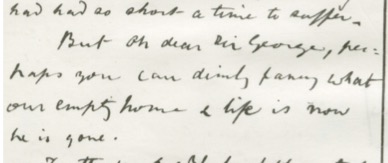

Only thirteen years later, Jemima movingly describes “her darling’s” death (on 17 August 1875), only a month previously, to his old mentor Sir George Grey: her grief all too apparent.

Based on her 1862 letters it seems that as soon as Jemima finds the “loving care and protection” of a husband and her own happy home, she also finds the “loving confidence” both she and Wilhelm hoped she would [C4.10]. By the time the “Bushman researches” begin, and are continued after Wilhelm’s death, Jemima is capably managing the Bleek and Lloyd household, assisting with the language studies and taking care of the numerous people living there – including her ailing husband and |xam and !kun instructors – ably supported by her sisters.

LUCY LLOYD

A distinct portrait of Lucy Lloyd emerges from Jemima’s and Wilhelm’s letters despite her not being their main protagonist. In them, and particularly at the start of the courtship correspondence, Lucy is described as a rather frail, nervous figure. But by the end of the short period covered by these letters Lucy seems a far stronger personality. (Lucy’s own letters and ship’s journal are not included here, but they show her in a more complicated light, complementing the rounded picture of Jemima we get in her letters.) *

Lucy makes her first appearance early on in Jemima’s courtship letters to Wilhelm (although Jemima almost certainly spoke of her when she and Wilhelm developed a friendship at Mrs Roesch’s). Jemima’s references to her older sister tend to focus on her poor health – and the extremely long “chronicles” she sends which Jemima struggles to read and respond to in kind while visiting about in England. We get the impression that Lucy sorely misses her sister, who she has hitherto shared a house with in Natal (and like Wilhelm probably finds Jemima’s rushed, too-short letters inadequate). Jemima writes that their bond is more than that of sisters: they were made “one by both disposition and circumstances” and are almost each other’s “second self” [C8.9]. Later, when the engagement becomes a certainty, Jemima assures Wilhelm of Lucy’s approval of him – and willingness to “give” him Jemima, her “most precious thing she has left on earth” [C8.19].

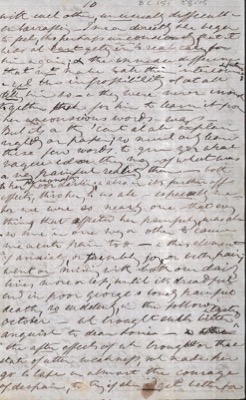

Lucy’s role is central to Jemima’s account of their traumatic shared Natal history. In a notable letter of 24 February 1862, written shortly after receiving Wilhelm’s proposal, Jemima explains what was for the sisters a “very painful reality then”. Apart from providing Wilhelm with the particulars of her history he requested to better know her and her family (he also asks Lucy for a chronicle of her Natal family’s “position”), Jemima needs Wilhelm to understand the source of her and her sister’s emotional pain, and their physical afflictions, as a means of explaining of why they are who they are – not least because the situation with their father is unusual and she worries he’ll be put off by it.

Over the course of many pages, and in an impassioned scrawl, Jemima describes how their father’s mistreatment of his daughters, their resulting mutual estrangement, and Lucy’s broken engagement followed by the “painful, lonely death” of her former betrothed, George Woolley, undermined her sister’s mental wellbeing to the point of despair; her mind becoming an “acme of doubt and perplexity” [C8.9]. Jemima’s descriptions of Loui’s mental state also convey her own state of mind, since the sisters are “so nearly one”. Their closeness led to Jemima experiencing “acute pain too”, affected by her sister’s “bitter and lasting anguish”, the “after-effects” of which brought on a “state of utter weakness” [C8.15].

Despite recovering from near-collapse after poor George Woolley’s death, Lucy’s physical health remained delicate a few years later when she made her way to the Cape to help Wilhelm prepare for Jemima’s arrival in the Cape from England. According to Jemima and Wilhelm’s notes to each other before the wedding, Lucy was often plagued by bouts of weakness and poorliness, brought about by exhaustion.

Early on in their correspondence, before their friendship becomes an engagement, Jemima encourages Wilhelm to go to Natal to meet Loui and her other sisters and to let her know exactly what he thinks of them – although she also wants him to love them as much as she does. She warns Wilhelm not to mind if her sister seems “very quiet and strange” at first, describing Lucy as “painfully shy and diffident sometimes” with a “morbid habit of self-depreciation wh a rather unfortunate and unhappy childhood and youth have given her”. Lucy also “believes herself very ugly and stupid and other equally flattering things” – echoing her sister and future brother-in-law in terms of self-regard [C8.5].

After reading Jemima’s account of her sister’s “fearful” experiences in Natal, Wilhelm’s sympathy and interest is roused. He writes to Lucy, wanting to become acquainted with one who is so dear to Jemima and to offer her “any small good, as a true friend’s sympathy can give”. Wilhelm is also fascinated by Lucy’s psychology. While he wants to help her recover from this “deep affliction” and attacks of "nervous vulnerability", to “be roused to higher considerations…and in the work which she has still to do, she will get her ultimate comfort“, he also can’t help analysing her response to her situation, wondering whether what happened with George Woolley was a result of an “overstrained sensitiveness”, “nervous susceptibility” or a "too morbid sensibility” (which he also recognises in Jemima), rendering her trials particularly “heavy on her” [C4.10, C4.12]. Wilhelm also observes that Lucy, like Jemima, has strong sympathies and antipathies, but his fiancée’s are not so strong or “eccentric” as Lucy’s, which developed that way due to the “necessities” of her life [C4.18].

Despite these characterisations, early on Wilhelm proclaims his confidence in “the dear girl”, despite at that stage only knowing her only through Jemima’s letters.

When Wilhelm begins writing to Lucy, he almost immediately regards her as a confidant, developing a close relationship with her in its own right and telling her almost “all”. He explains to Jemima that this is due to the sisters’ “oneness” of feelings, but one imagines he is also impressed by Lucy’s obvious intelligence and sensitivity in her letters – and possibly, like he and Jemima, her love of discussion and her critical sensibility [C4.10]. (Wilhelm and Lucy no doubt exchanged long letters narrating their health and other struggles and, in Lucy’s case, explaining her family’s history and “position”. These 1862 letters between them have not been located.)

After proposing to her sister, Wilhelm further demonstrates his confidence in Lucy as Jemima’s adviser and protector by insisting she only permit Jemima to enter an engagement with him after consulting her and thoroughly setting her mind at rest [C4.10]. Once the engagement is certain, despite his and Jemima’s fear of others’ interference and influence, Wilhelm confides in and relies on Lucy’s advice on all plans and announcements involving the engagement, Jemima’s Cape journey and dealings with their father and her Natal family. Shortly before the wedding he depends on her to help prepare for Jemima’s arrival from England, their marriage and their house – later describing her to her sister Fanny as “indefatigable” [C6.5].

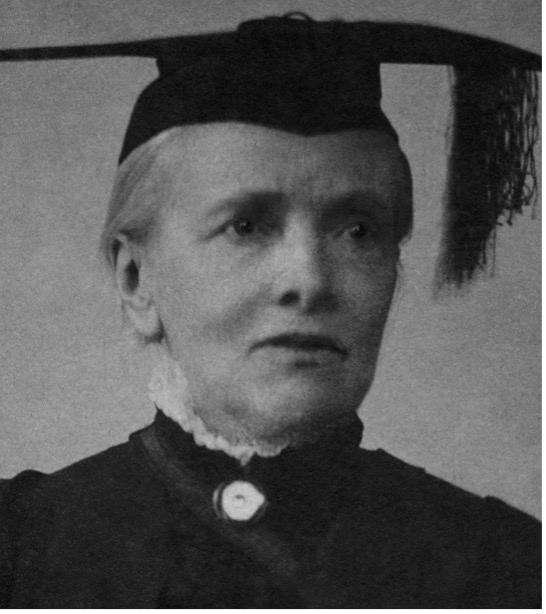

Ultimately, Wilhelm’s hopeful words in the 9 April 1862 letter were proven correct. By the time the |xam instructors arrived at Mowbray Lucy was indeed “roused to higher considerations”; well able to do “the work” which one hopes brought her “ultimate comfort“. She was strong enough to conduct the lion’s share of her and Wilhelm’s “Bushman researches”, then “keep on the Bushman work” when Wilhelm died as well as his labours at the Grey Library – in addition to helping a grieving Jemima with the household, publishing the research and fundraising for its continuation. Despite a lifelong tendency to poor health, Lucy lived until the very respectable age of 79, having completed her and Wilhelm’s “joint Bushman studies” and earning an Honourary Doctorate, conferred by University of the Cape of Good Hope in February 1913, for her efforts.

Sources

- BC151 C4.8 WB to JL 18 December 1861

- BC151 C4.9 WB to JL 19 January 1862

- BC151 C4.10 WB to JL 19 February 1862

- BC151 C4.11 WB to JL 23 February 1862

- BC151 C4.12 WB to JL, 9 April 1862

- BC151 C4.14 WB to JL 28 April 1862

- BC151 C4.18 WB to JL, June/July 1862

- BC151 C6.5 WB to FL 30 October 1862

- BC151 C8.2 JL to WB 30 May 4 June 1861

- BC151 C8.4 JL to WB 4 August 1861

- BC151 C8.5 JL to WB 19 August 1861

- BC151 C8.6 JL to WB 4 October 1861

- BC151 C8.7 JL to WB 4 November 1861

- BC151 C8.8 JL to WB 4 December 1861

- BC151 C8.9 JL to WB 29 December 1861

- BC151 C8.10 JL to WB 4 January 1862

- BC151 C8.13 JL to WB 30 January 1862

- BC151 C8.14 JL to WB 30 January 1862

- BC151 C8.15 JL to WB 24 February 1862

- BC151 C8.17 JL to WB 2 April 1862

- BC151 C8.18 JL to WB 13 April 1862

- BC151 C8.19 JL to WB 2 June 1862

- BC151 C8.20 JL to WB 10/16[?] June 1862

- BC151 C8.22 JL to WB 3 September 1862

- BC151 C10.17 JB to Sir George Grey 7[?] September 1875

- BC151 C4.1 WB to JL 15 May 1861